It’s important to choose an appropriate level of investment risk and return. This video will help you understand stock market risk and whether stocks get safer with time. They don’t.

Rule #3: Control investment risk and return

In the first two episodes, we looked at developing a plan and your most important habit—saving for your goals. In both those episodes, we looked at the risk of inflation and introduced ways of hedging that risk with I bonds and T.I.P.S. Stocks are another way to achieve that, but they introduce substantial new risks.

This episode will help you understand stock-market risk. I help you understand why stocks don’t get less risky by owning them longer. I want you to understand well enough that you can explain this to your friends.

Also, learn about bond market risk and how to allocate between stocks and bonds.

Hi, I’m Rick Van Ness. You’re watching The Ten Rules of Common Sense Investing1 to maximize lifelong happiness. These rules help you answer two big questions:

- How much to save? and

- How much risk to take?

Stock investment risk and return

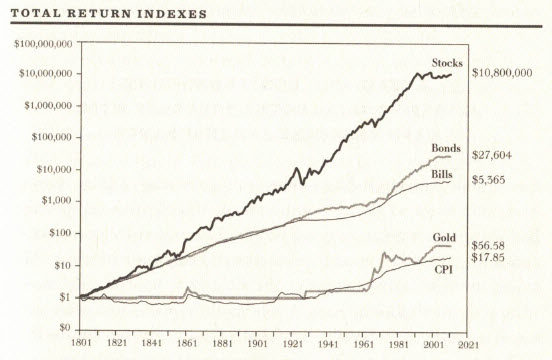

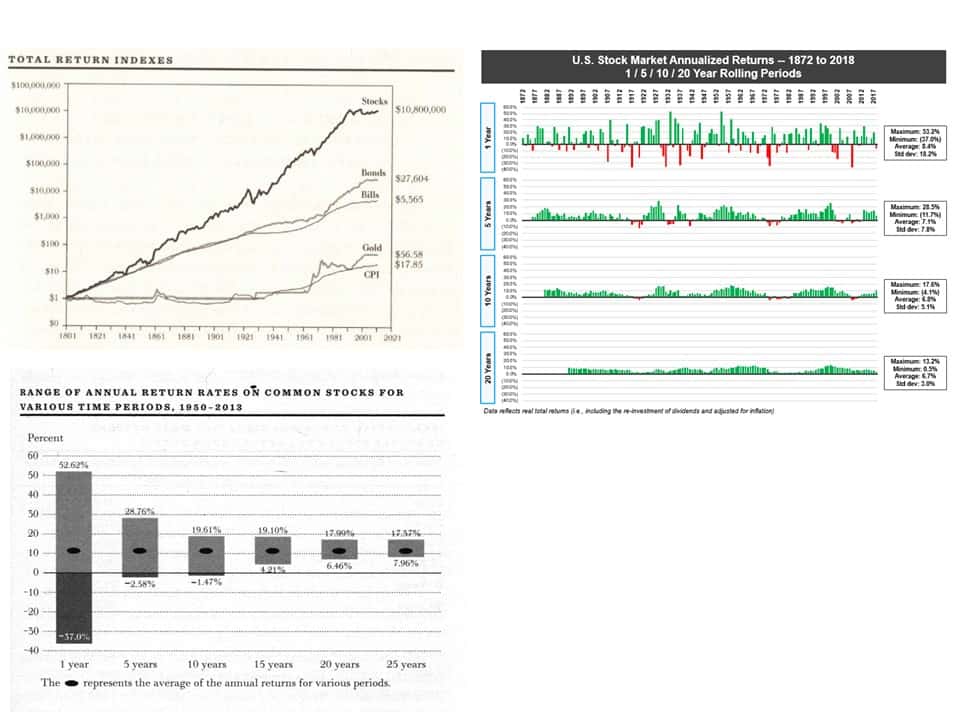

Here’s a chart I like.2 At a glance you can compare the total returns for stocks and bonds. Risk and return go hand-in-hand.

KEY POINT: higher expected returns come with higher risks.

The bond market is much bigger than the stock market. And yet, stocks have substantially outperformed bonds over the last two centuries. Why wouldn’t all these bond owners prefer stocks for their superior returns?

Think of bonds as loans. You loan your money to a company or the government that they pay back with well-described terms. There is great certainty.

Stocks are ownership of businesses. The upside for investors comes from the profitability and growth of those businesses. But there are no guarantees. Investors take a much higher risk for much higher expected returns.

Even a well-diversified stock portfolio can lose half of its value in any year.

This year is a vivid example of the stock market plunging. This happens regularly. It’s unpredictable, but the stock market is always reflecting our collective best estimate of the future profitability of these businesses.

Some of you are thinking, “I’ve been here before and the stock market always recovers quickly.” In other words, you’re safe if you are a long-term investor.

Here are the last three decades of the Japanese stock market3 to show a counterexample. Larry Swedroe emphasizes that investors, particularly individual investors, should “never treat what may seem highly unlikely to them as impossible.” That’s why the very first episode in this series had you look at what you need money for and when.

Do stocks become safer with time?

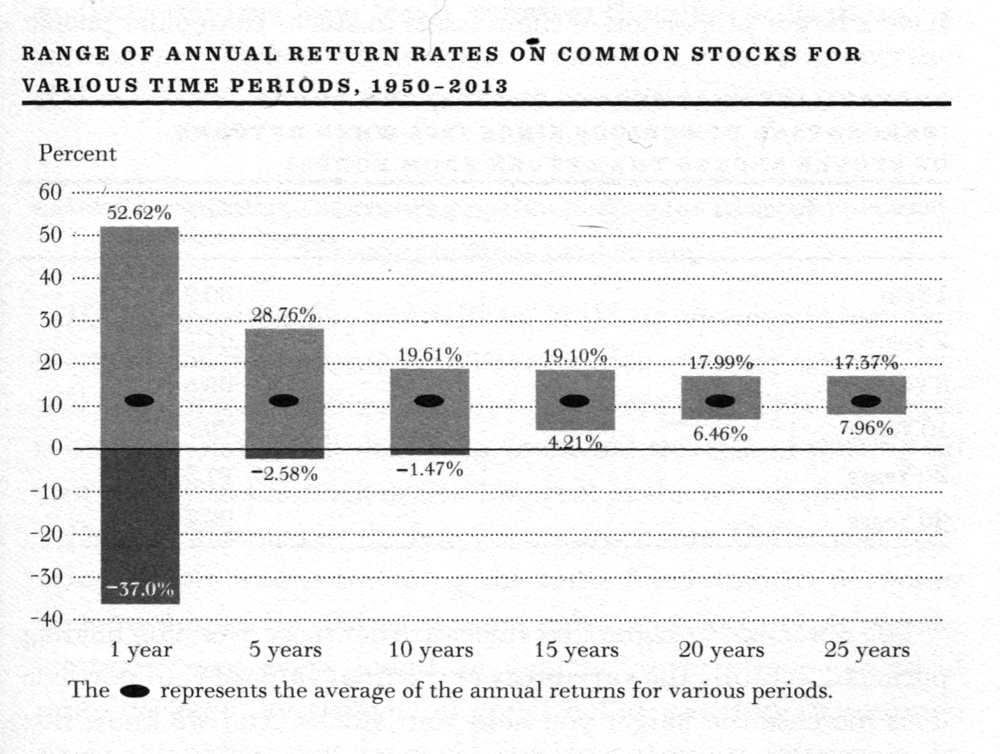

Charts like this next one are very common.4

This means the 1-year returns, for all the years they studied, had an average return of about 10% and a range of values from up 53% to down 37%. This chart seems to promote owning stocks for their greater return if you can own them for 15, 20, or more years—that time erases risk, which it certainly does not.

If you look at probability without regard to consequence, there is some truth to this. A diversified portfolio of stocks does become increasingly more likely to do better than risk-free investments.

But, my goal is to strengthen what you already know intuitively — that in any upcoming day, week, or even year, stocks will be riskier—far riskier—than short-term U.S. bonds.

Follow me here. The deviations from the average rate-of-return disappear when many years are averaged together. This chart is statistically true but often misinterpreted to mean that risk somehow magically gets erased when you own stocks for a longer period.

What investors are concerned about is the amount of wealth they will have at a future date. I’ll show you that the range of final values increases with time.

What’s missing on this chart is the uncertainty of future returns. This chart says nothing about the future, only about the past. Unlike bonds, there’s no predestined rate-of-return with stocks. The risk is the possibility that, in the long run, stock returns will be terrible and you don’t meet your goals.

Uncertainty increases with time.

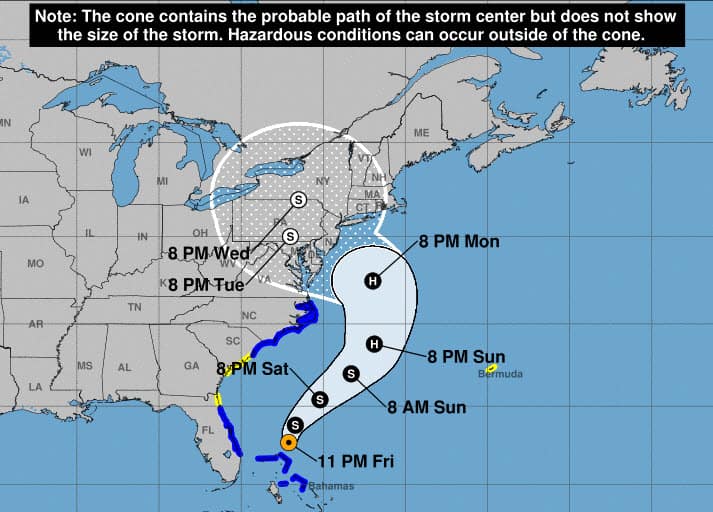

Predicting the future value of your stock portfolio is much like predicting the path of a hurricane.5 Uncertainty increases with time.

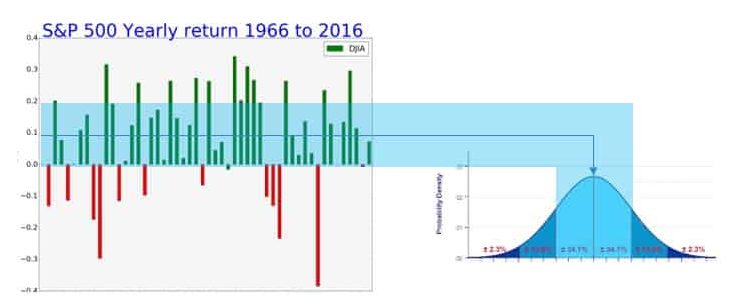

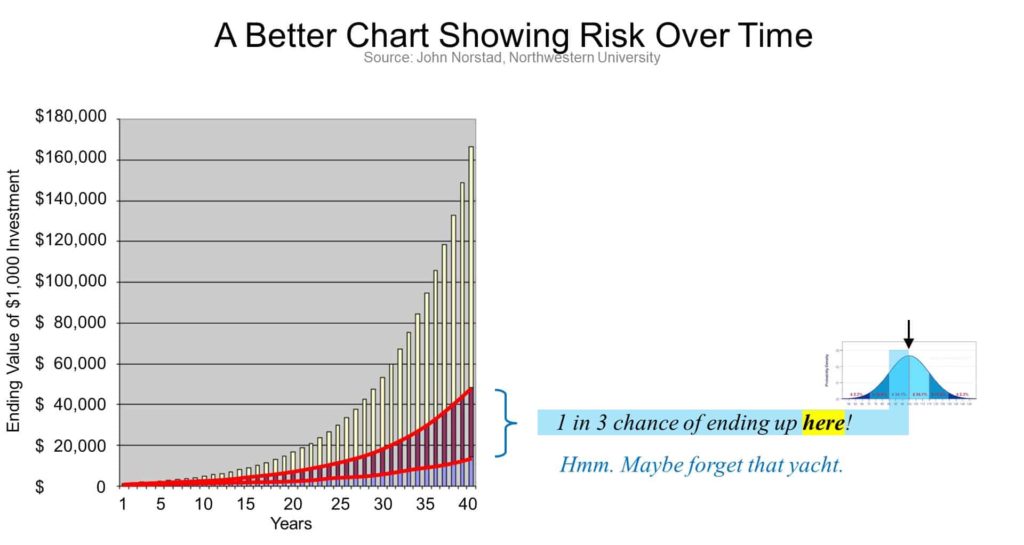

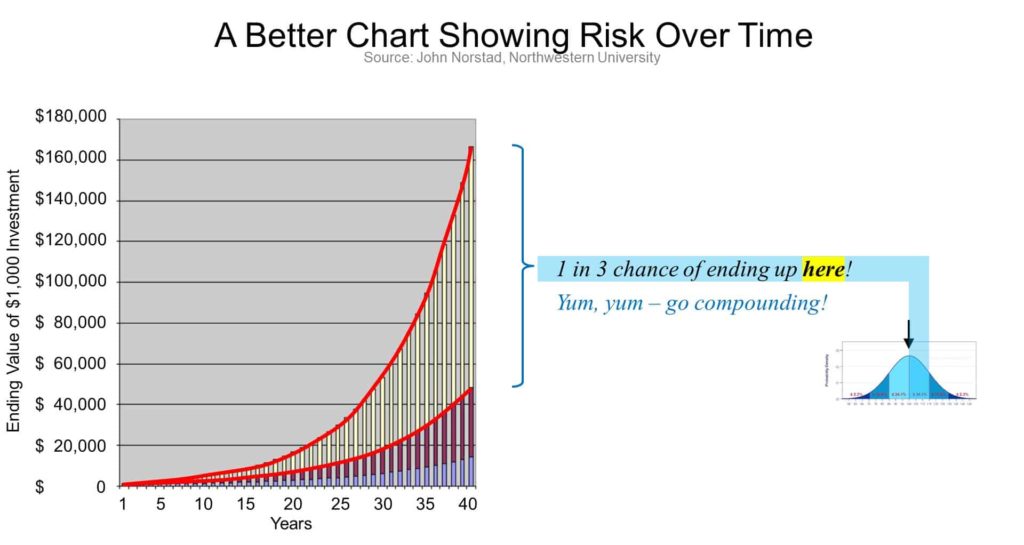

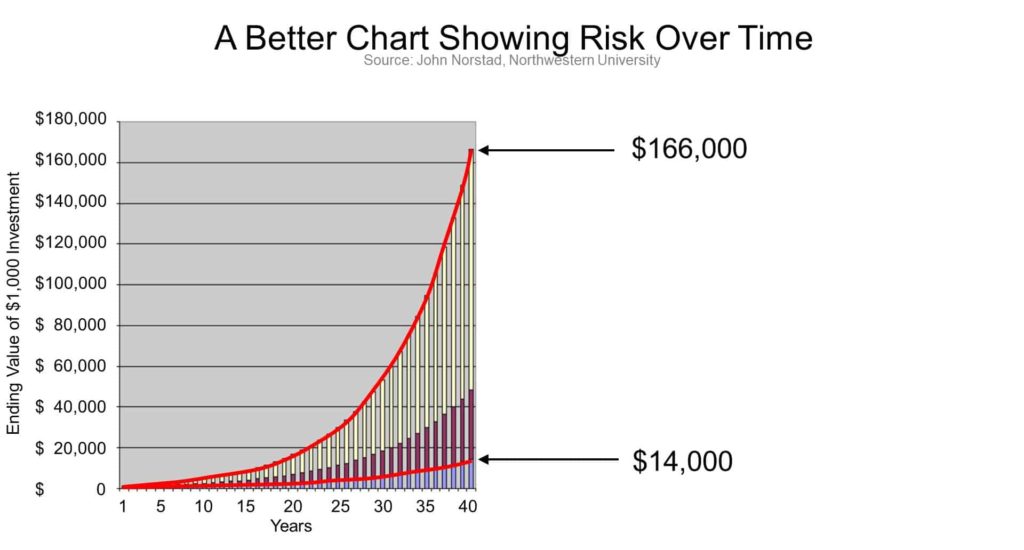

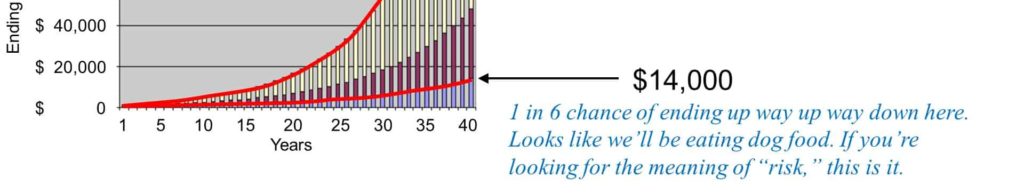

John Norstad shows this visually in a compelling article by representing actual S&P 500 returns as a normal distribution.6 I’ll explain here.

Stock returns vary widely, but they do have an average value. And 2/3 of the returns are within one standard deviation of that.

Let’s use that and look at the possible end values of investing $1000 over time horizons ranging from 1 to 40 years.

We have a 1 in 3 chance of the final value in this slightly disappointing range.

Also, a 1 in 3 chance the final value is in this range above average.

That means if the stock market performs as it did I the past, we have a 2 in 3 chance that the ending value will be somewhere between $14,000 and $166,000. This is an enormous range of possible outcomes.”7

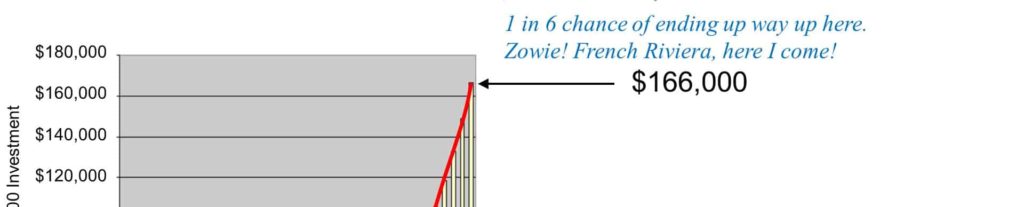

There is even a 1 in 6 chance that you’ll end up higher. That’s the miracle of compound interest.

But that also comes with a 1 in 6 chance that you’ll end up somewhere near the bottom.

KEY POINT: it is the total return that matters.

“Now this chart is revealing. Because for an investor concerned with the value of his portfolio at a future date, it is this total return that matters, not the annualized return.”8

To recap this section about stock market investment risk and return:

- Stock returns are high because they are risky.

- Stocks are just as risky tomorrow whether you have owned them 1 year or 10 — if measured by volatility.

- Short-term volatility may not be a concern to long-term investors with a safety net, but it certainly is for individuals with upcoming spending needs.

- Lastly, the range of possible total returns increases over time.

Test Yourself. Fooled by statistics?

Has this made sense so far? Then test yourself — because most people are still misled by statistics.

In this animation, you can see how U.S. stock market returns have trended when we look at 1 / 5 / 10 / 20 year rolling periods.9

Taking a 1-year view, we see lots of red — there were plenty of years in which the market was down.

As we take a longer and longer periods (from 5 to 10 to 20 years), the range of possibilities narrows, and the chance of losing money diminishes. Or does it?

By the last line, where each of these green lines represents 20-years, you won’t see any more flashes of red. Their message is, “The U.S. stock market has never lost money over any 20 years.”

OK. Tell the truth. Does that not scream out to you that the stock market becomes safer in the long run? What could go wrong? Right?

Can you see that these two charts are presenting the same information in two different ways?

What we are watching here is, once again, merely a demonstration that stocks produce a superior average return in comparison to safer investments.

KEY POINT: stocks produce a superior average return compared to safer investments because they are riskier. Investment risk and return go hand-in-hand.

This is what we have seen before, and that’s as it should be because the higher return compensates investors for taking the added risk.

But this does not mean that stocks become less risky over long time horizons. The risk is that the stock market might be down when you need to pull your money out.

I think you can understand intuitively that the idea that “stocks become safer with time” is a fallacy. Yet, this notion remains widely misunderstood. You’ll be doing your friends a favor if you could enlighten them.

I’ll provide links in the transcript if you want to dive deeper. Professor Zvi Bodie has a compelling argument with his proof using option pricing.10

But now, let’s look at some practical questions and incorporate wisdom from some additional experts.11

Need stocks to accumulate more wealth?

First, do you need stocks to accumulate more wealth? For lifelong happiness, we need to be able to spend money today as well as save enough for a potentially long retirement.

It’s true. The probability of accumulating more wealth is greater using stocks than with risk-free I bonds. But, it would be an error not to consider consequences.

For instance, you would probably also accumulate more wealth if you didn’t pay for fire insurance for your house. I mentioned this in episode 2. Unlikely events that are highly consequential are perfect for insurance.

This question is essentially asking whether you could save less by investing in stocks. Maybe, but choosing to invest that in risky assets for a better return could have a disappointing outcome.

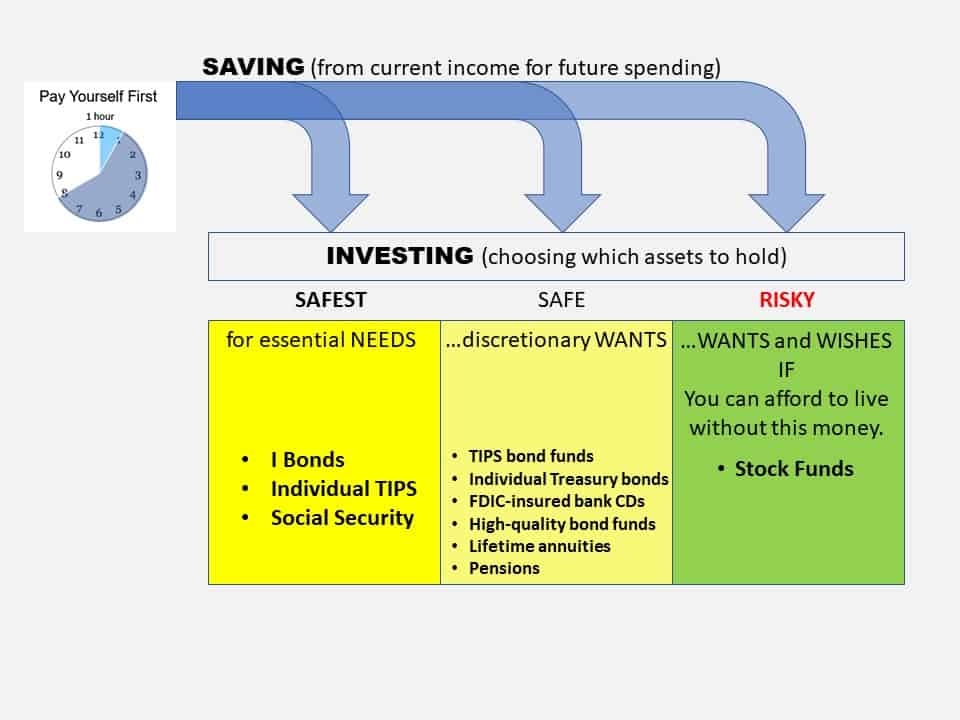

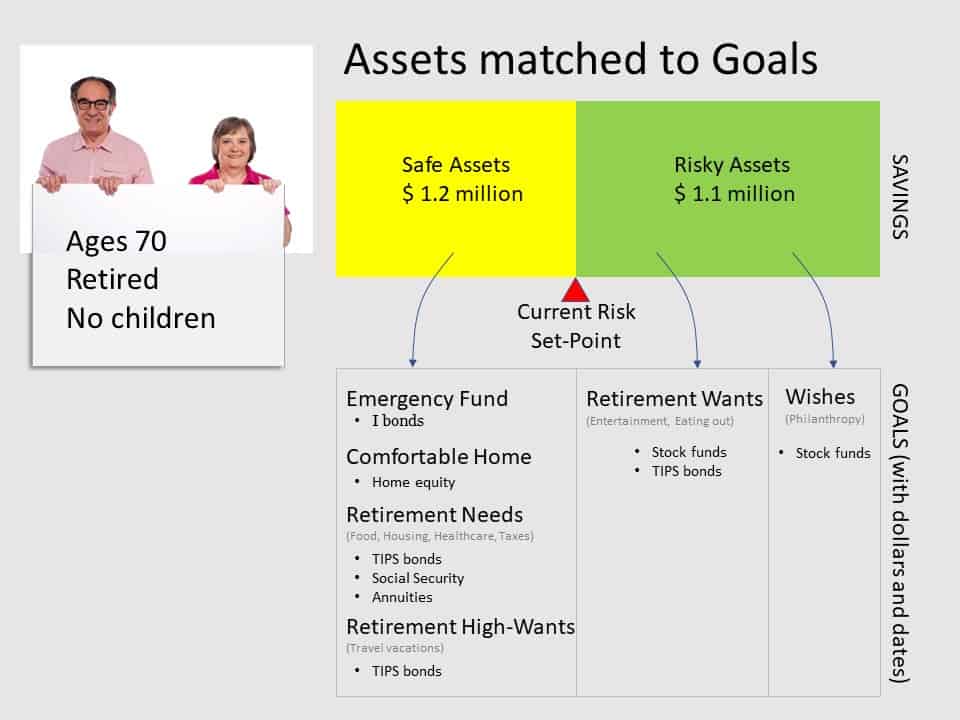

The practical way to do that, writes Dr. Bodie, is to separate your goals into needs and wants. Lockdown the income to meet your essential needs and important goals by matching them with safe investments. Keep your risky investments allocated to your wants and wishes—that you could live without, if chance works against you.12

What about stocks for young people?

What about stocks for young people?

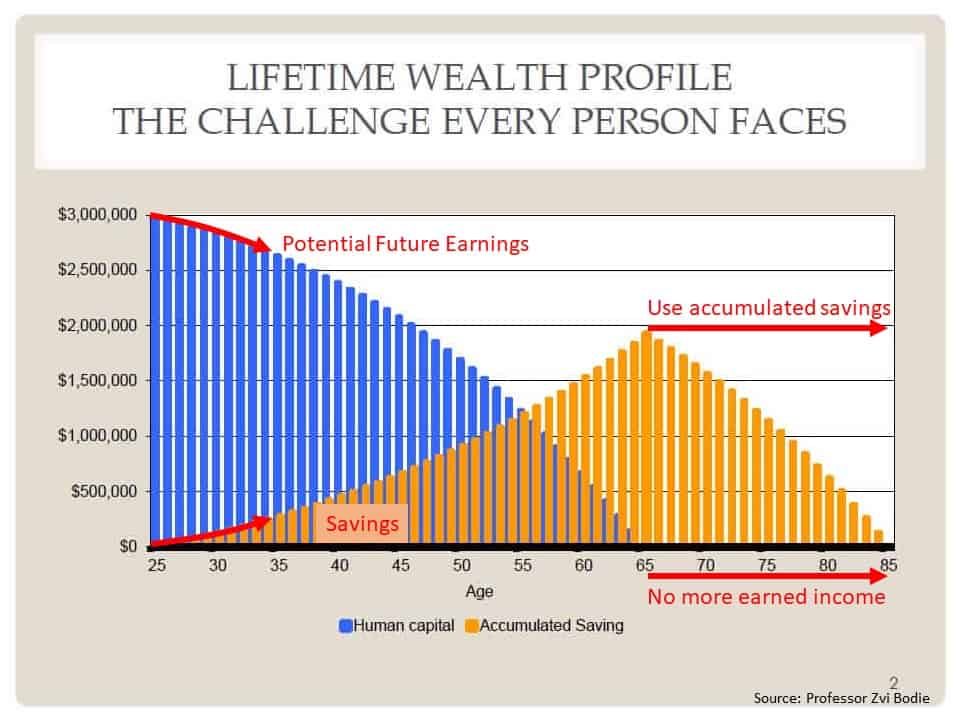

Here, Professor Bodie agrees that age does matter, but not because of the commonly mistaken idea that the stock market becomes safer over long holding periods. Rather, younger people have a longer time horizon to build wealth through work. He explains this with a simple life-cycle model.

All your future earning power starts high and gets depleted when you retire.

What you save for future spending becomes accumulated wealth.

Your total wealth, at all times, is the sum of your potential future earnings and your accumulated savings. So, you can see that if their accumulated savings are in risky investments, that’s only a tiny fraction of their total wealth when they are young. The consequences of loss are small.

But if your future-earnings capacity is weak, or you are near retirement, then the consequences of loss are hard to recover from.13

William Bernstein warns against staying invested in stocks after you’ve met your goal, saying:14

When you’ve won the game, why keep playing it? The risks for a retired person can be nuclear-level toxic.

William Bernstein

Which brings us to this next good question.

Bond investment risk and returns

How risky are bonds?

How risky are bonds? How risky are bond funds? First of all, compared to the stock market, bonds are much simpler!

Stock risk is intuitive

If you own a stock fund, you own a slice of all publicly traded businesses. You get that.

Your companies try to create value for customers. That’s their purpose. And the value of your shares is the market’s prediction of those future earnings. You get that too.

A lot can go wrong: company management can change, workers might strike, competition, government regulation, pandemics. You get all that too.

Stocks are complicated. But people have a pretty good intuitive understanding of them — other than wishful thinking — that they’ll be safe as long-term investors.

Bonds are much simpler

Bonds are much simpler than stocks. But new investors find bonds less familiar and therefore a little confusing. I have a separate video series about bonds. But for now, I want you to think about them like a bank CD. You are comfortable with how they work, right?

A bank CD is a simple form of a bond. You loan your money to the bank. They pay you a fixed interest rate for the use of your money for the term of the loan. You know exactly what you are getting with a bank CD. You can depend on it.

Then, you tell me that you could loan your money to your cousin for a higher rate. Now you get the idea! That would be called a “junk bond”. They are marketed as high-interest bonds with lower credit quality.

Bond funds are a convenience

You’ll have the option of letting a bank CDs roll over into a new CD at the prevailing rates when they mature. If you own a whole bunch of them you essentially have a bond fund. Bond funds are a convenience. The quality of the bond fund is as good as the bonds that comprise it.

When interest rates change, it causes the bonds or CDs you already own to temporarily be worth more, or less. You can eliminate interest-rate risk by holding individual Treasury bonds or CDs to maturity, or by choosing short-term bond funds. Further, you can eliminate default risk by sticking with the highest quality bonds. Eliminate inflation risk by choosing inflation-indexed bonds.

Key Point: Bonds can provide great certainty compared to the stock-market!

Bond funds are perfect when the role of bonds is to stabilize your portfolio for some long-term goals. Individual bonds and CD’s are perfect when you can match their maturity with when you will need that money for a specific goal.

How should we allocate between stocks and bonds?

Own Your Age in Bonds.

John C. Bogle

John Bogle famously said: “Own your age in bonds.” It is memorable, and therefore useful. It is a starting point until you have created a workable plan for yourself. This has its limitations, but it does reduce your exposure to the stock market as your future earning potential decreases. Adjust that to fit your situation.

Asset allocation is an important decision, but there is no perfect answer. Close is good enough.

Choosing between risky and safe investments is a goal-by-goal decision. Prioritize your goals. Every situation is different.

It’s not age that needs to drive this, but rather considering both the probability and consequence of market drops. How much do you stand to lose? How severe would be that loss? Your spending goals have fixed dates and dollar amounts. You should never put at risk what you cannot afford to lose. Some more examples might help clarify this:

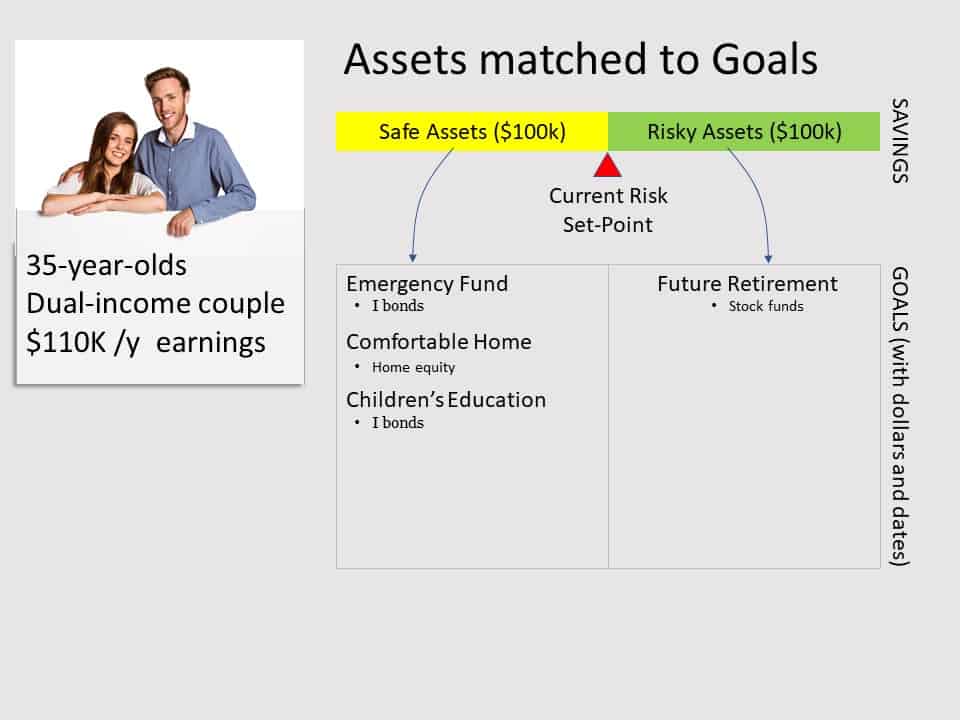

This 35-year-old couple is just entering their prime earning years with secure jobs and can afford to take a risk in their investment portfolio for their retirement 30 years away. Meanwhile, they have other important goals that they don’t want to risk in the stock market.

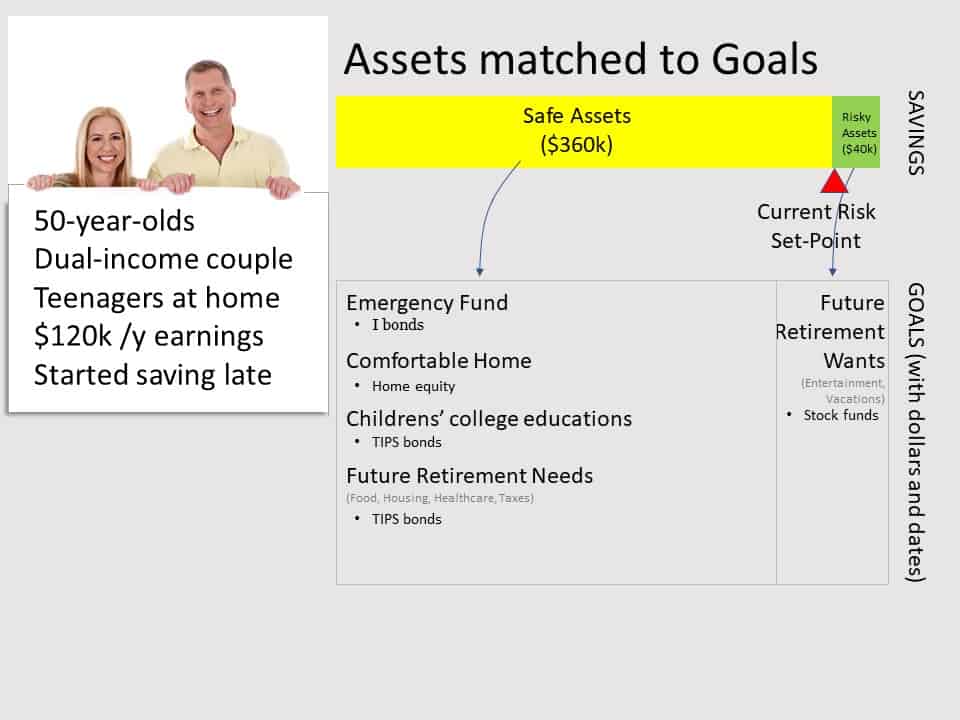

This couple started late. They are tempted to accept investment risk and try to catch up, but they remember 2008, and now 2020, and know that could happen again at any time. So, they are focused on building a safe floor of income plus pay for their kid’s imminent college educations.

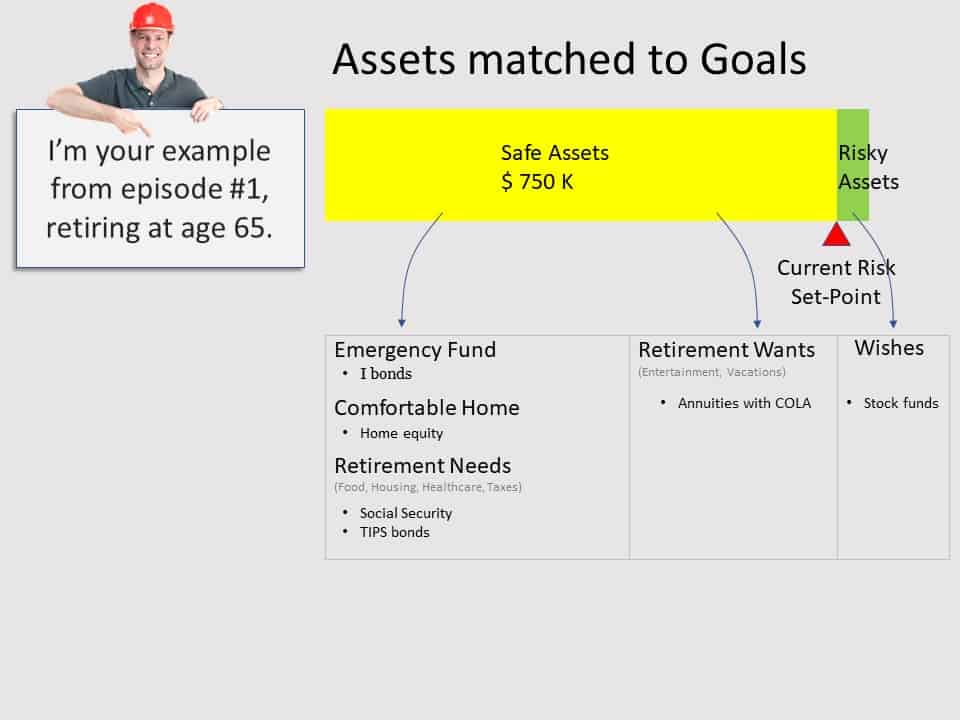

Here’s the example we developed in the first two episodes. He set himself up to be completely worry-free using delayed Social Security and an annuity to eliminate the risk of outliving his money.

This couple is retired with no kids and all their essential needs met, plus more than enough for both their retirement “needs” and “wants”. Their remaining investments are intended for charitable organizations.

SUMMARIZE

In summary, both stocks, and bonds can be appropriate for your portfolio — if you have your eyes-wide-open about investment risk. The next video begins to look at how to go about choosing a stock fund.

It turns out that you won’t get a higher expected return for certain kinds of risk that can be diversified away. Learn that there is a “best portfolio” of stocks that will produce the highest return for any level of risk taken. All that in the next episode about diversification.

See you in the next video.

Investing for beginners video series

▼The Ten Rules of Common Sense Investing is a series to teach investing for beginners:

🠞 The Smart Investing for beginners summary guide

https://financinglife.org/smart-investing-for-beginners/

✅ Rule #1: Develop a workable plan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P38tR8IoTGI&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #2: Start saving money early

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=08s12IUc-Lc&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #3: Control stock market risk exposure

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCeB7_sn4ZM&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #4: Diversify stocks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zXnbxLtRhrU&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #5: Never try to time the market

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3pnpbWYfwc&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #6: Use index funds when possible

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GF5vThMkF-U&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #7: Keep costs low

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqQfA4xPvAo&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #8: Minimize taxes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLDJN-sbhuA&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #9: Keep it simple

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmUJeDRGi2k&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

✅ Rule #10: Stay the course

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHi2RdQ81Yk&list=PL21534875BFC50EEE

Recommended books related to investing for beginners:

- The Bogleheads guides

- My book review of Zvi Bodie’s book: Risk Less and Prosper

- My book recommendations

- Links for TIPS and I bonds (and links within this article!)

Endnotes for Rule#3: Investment risk and return:

1. This series of ten rules is also endearingly called the Boglehead Investment Philosophy — investing advice inspired by John C. Bogle. I prefer to call it Common Sense Investing as a nod to one of my favorite books by John C. Bogle.↩

2. Burton G. Malkiel, A Random Walk down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing, Rev. and updated ed (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2011), 305.↩

3. tradingeconomics.com/japan/stock-market ↩

4. Walk down Wall Street, p. 363.↩

5. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutcone.shtml↩

6. Risk and Time, John Norstad, Northwestern University, https://web.archive.org/web/20170911171611/http://www.norstad.org/finance/risk-and-time.html↩

7. Risk and Time, John Norstad, Northwestern University, https://web.archive.org/web/20170911171611/http://www.norstad.org/finance/risk-and-time.html↩

8. Risk and Time, John Norstad, Northwestern University, https://web.archive.org/web/20170911171611/http://www.norstad.org/finance/risk-and-time.html↩

9. annimated gif https://themeasureofaplan.com/us-stock-market-returns-1870s-to-present/↩

10. Risk and Time, John Norstad, Northwestern University, https://web.archive.org/web/20170911171611/http://www.norstad.org/finance/risk-and-time.html↩

11. The Riskiness of Stocks: Readers Protest—and the Authors Respond, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443324404577595483877996626↩

12. Zvi Bodie and Rachelle Taqqu, Risk Less and Prosper: Your Guide to Safer Investing (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2012).↩

13. The Riskiness of Stocks: Readers Protest—and the Authors Respond, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443324404577595483877996626↩

14. Interview in WhiteCoatInvestor podcase, https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/bernstein-says-stop-when-you-win-the-game/↩