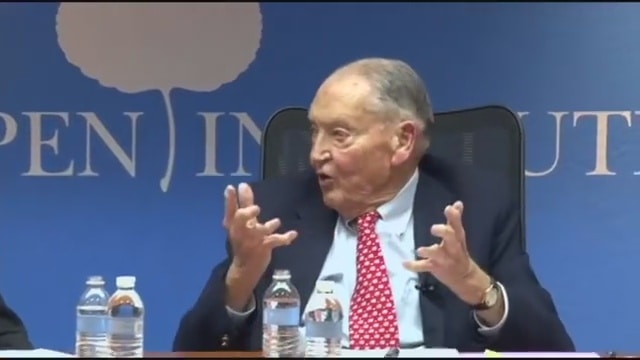

In this conversation John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, is asked about investing in the stock and bond markets. While his comments were delivered in 2015, the wisdom is still valid today (2019). I have created a summary and transcript to help you find spots that interest you and make the best use of your time. This video was produced by The Aspen Institute who describes their video as follows:

The Investment Gospel According to Jack Bogle: “Don’t look for the needle in a haystack. Just buy the haystack.” Does that mean buy, sell or hold — stocks, bonds or gold?

Watch this discussion with John C. Bogle, who founded The Vanguard Group in 1974, served as its chairman and CEO until 1996 and senior chairman until 2000. Fortune magazine named him one of the investment industry’s four “Giants of the 20th Century”. TIME magazine cited him as one of the world’s 100 most powerful and influential people.

Known for his straight talk on Common Sense Investing, and for having invented the Index Mutual Fund, Jack Bogle built Vanguard to be the world’s largest mutual fund organization, representing 170 funds with current assets totaling more than $2 trillion. He has written 10 books, received honorary degrees from 14 universities, served on many important commissions and boards, received countless honors, and to tally changed the face of investing in the world.

Summary of video: Bogle on stock and bond markets in 2015

John Bogle offers long predictions about the stock and bond markets, and answers questions about Vanguard other topics including:

- What is going to happen to the stock and bond markets next year?

- What is your prediction on inflation, and what investors should do about inflation?

- What are the secrets behind the enormous success at Vanguard?

- Any thoughts about activist shareholders hurting long-term investors?

- Are you concerned about how the market is changing with high-speed trading?

- How do capitalization-weighted mutual funds compare with “smart beta” funds?

- How do you feel about the consumer financial protection agency?

- How can we handle our 18 trillion dollar deficit increasing a trillion dollars each year?

The following transcript is my best effort to help you use your time wisely. Simply drag the progress marker in YouTube to the time of interest and listen to the comments directly.

Transcript of video: John Bogle comments on the stock and bond markets in 2015

Speaker 1: Jack, I speak for all the fellows, they’re just delighted to have you with us and thank you for making the effort to come all the way down here to the woods on the eastern shore, to this modest of a residence that we have here.

Jack: It reminds me of my own.

Speaker 1: Let’s begin with a very easy question and one that’s on everybody’s mind in this room, though they wouldn’t admit it. What’s going to happen to the equity and the fixed income market in 2015? Should we buy or sell, just hold on to our existing investments? And, if we do that, then cancer our subscription to the Wall Street Journal?

Jack: If I may, first let me thank Phil for the introduction, a lovely introduction and thank Judy for being such a great arranger of getting me down here. It’s wonderful to be here. I should say with all due deference, Phil, the book sales in the last two weeks have been three weeks, I get four weeks now, have been slightly, only slightly, I’m sure Aspen is responsible for most of it, only slightly by the fact that Warren Buffet recommended it in his annual report this year. You probably are the laboring oar though, but I don’t know. It’s amazing. This is a book that just celebrated its eighth anniversary. It’s been number one on the Amazon mutual fund list. It’s not exactly 50 Shades of Grey, but it’s been on there and it still is on there now. It’s pretty exciting to have it go on like that and then get a nice boost from Warren. It’s amazing to me. I did the best I could with it. I don’t usually write the popular kind of … I tried to write it in the most basic simple way, and it’s not so easy for me. I’m not the best writer in the world, but it’s great to see it do well and get, has 300 comments on Amazon or something like that, pretty good. It makes me very happy.

(Watch on video starting at 2:09)

Question: What is going to happen to the stock and bond markets in 2015?

That’s good background. Now, I’d like to tackle, answer your question. A little belatedly. Number one, we’re obviously living in a world where there’s a crisis around every corner. I don’t think it’s a much riskier time actually in a long, long time in our world around us. You know I want to enumerate things because you’re probably better, more familiar, with these events around the world and then the country than I am. It’s very risky out there and the stock and bond market are saying there are no risks out there. The bond market presumably because of the FED, not presumably but certainly because of the FED holding rates down. The stock market influenced by that because people have to choose between stocks and bonds. If bonds get less attractive, this is part of the FED’s great design, they think it’s their responsibility to raise the asset prices so we’ll spend more if we’re lucky enough to have assets. It’s a risky time, and not reflected in the market.

I should be quite blunt and say I have never, I repeat, never recommended what the market will do in a given year because I have no idea and I don’t know anybody that can do market timing that way. I don’t even know anybody who knows anybody who’s going to ever be successful market time. That’s just not my game. My game is to realize a very important thing about the stock market, I’ll come to the bond market in a second. That is in the long run the stock market is all about the returns earned by American business. I have a little formula that I use, put together myself, not very much copied, but highly accurate. The returns by American business are reflected in A, the current dividend yield and B, the earnings growth that follows. B, there’s speculate return, two I should say, there’s speculate return, which is that people are going to pay a lot more for stocks or a lot less if the stock price earnings multiple, the price people pay for a dollar of their earnings goes from 10 to 20. That’s a 50% increase and that’s 7% ear over a decade. That’s why times were so good in the ’80s and so good in the ’90s and so poor in the 2000s. It’s all the math of the market.

You can’t guess anything in the short run. I do my work on … looking out in decade long links. I’ve been doing it since the early 1990s and it’s been quite accurate. Timing has always been a little bit off, but that’s where the market returns come from. Fundamentals and not speculation. Where are we today? Today the dividend yield is 2%. I think if we’re lucky we’ll get 5% earnings growth in the next decade. That’s a 7% investment return to the stock market and we have to take in the price earnings multiple is high, relatively high, not super high, at 20 and it will probably go down to something like 15 because when it gets to 20 it’s more apt to go down than up over a decade. That kind of a change, from 20 to 15, 25% decline is about 3% a year off that 7% return I described. That’s a 4% nominal return on stocks. When you take inflation out, it’s 2%. Here’s the good news for all of you, we’ll come back to this later. Take the expense ratio, the typical mutual fund out of that which is 2% and you are left with a nominal return of zero. You’re all with me on the math.

Let me just give you an example if I may from common sense, written at the 2007, the book was published in 2008. I went through this exercise and I have a chapter in the book called, “What happens when the good times no longer roll?” I said we’re not going to get the same kind of returns we’ve had in the past because of this math and I took them through a little chore and I showed you. I came out with a 7% return for the next decade. We’re seven years through that decade and the return has been, he said with a little pointed pride, 6.8%. It’s helpful, the timing is not always good, but I think it’s quite clear we’re not going to have that kind of markets we’ve got in the past. Most of the people who’s opinions I respect are going to agree with me on that.

The bond market, it’s the simplest thing in the world, looking at the returns for the next decade on the bond portfolio is a 91% probability of reflecting the interest rate when you buy in today’s interest rate. If you want to buy that ten year treasury, intermediate term bond, a little less than 2%, you’re highly likely to get something 1.5% and 2.5% over the next decade. There’s no way around the math because it’s the interest coupon that drives it. I’m not very optimistic about future returns, but you’ve got to tell the truth about it. What do you do about it? First, never in the market or out, an unsatisfactory question. People are trying to do that, time the market totally. All cash today, all stocks tomorrow. I don’t mean to be crude, but they should have their heads examined. Did I make my point clear?

It’s really what your stock/bond ratio should be. I don’t believe in commodities and gold because they have no internal rate of return, like I described for the interest rates on bonds and the earnings growth and dividend yields on stocks. You’re just betting that you can sell them for more than you buy it. That is what we call speculation. If you’re concerned, and there’s good reason for concern and you tend to be, I think most people should focus on more or less a 60/40 … 60% stock, 40% bonds. At Vanguard we have a balance fund that happens to have that profile I guess because I picked it. You want to lean a little bit to be 50/50. I would not take 60% equities, up to 70%. I could be wrong. If I knew everything I would be 100/0 or 0/100, but I’d say lean to the conservative side and don’t pay much attention to the bloody stock market. I have a sentence in my book, a little book of common sense investing that says that the stock market is a giant distraction to the business of investing. Think about that. What are we watching every day? Sooner or later the returns regress to the returns of the business total and those are the returns of the economy. It’s not very complicated. I know that was long, but I didn’t want to answer it in a flip way.

Speaker 1: That was terrific and there was a lot. I can see people were listening carefully. Let’s shift gear and talk a little bit about Vanguard, which is truly one of the great corporate stories of the last 50 years and one I think we all would like to maybe from your perspective and looking back a little bit … As we said, you started Vanguard a little over 40 years ago. What was the state of the mutual fund industry? You I believe were in the industry, then started Vanguard. What drove that and what was behind that decision?

(Watch on video starting at 9:40)

Question: What drove you to start Vanguard 40 years ago?

Jack: The industry that I came into in 1951, I got right out of Princeton University, went to work for Wellington Management Company. In the middle of toe go-go era, mid to late 1960s when lunatic stocks were highly valued, it was just an insane era, almost like the information age or high tech area or internet area that was supposed to come back at the end of 1999, beginning at 2000. When I came into the industry I looked in industry that was pretty good. There were about 75 stock funds, nothing beyond that. They all looked pretty much the same and they all looked a little bit like the Dow Jones industrial average. They all performed more or less the same because they weren’t taking big risks, they were staying right down the middle. They had a record that would lag the market and did all the work in my Princeton thesis, which I wrote on this subject back in 1951. It was a thesis that was very optimistic about this industry at a time when it was tiny, two and a half trillion dollars, and had the great hope it had for channeling the savings of Americans into the productivity of American business.

Not a very complicated thesis. By the time 40 years ago comes, I’ll go back a little bit before that, this in 1966, the middle of that go-go era, mister Morgan, the founder of Wellington Fund and the head of it, owner of it, although it was publically held partly by then, came to me, said, “Jack, I want you to take over the company and do whatever it takes to get it fixed,” because we were a very conservative company and this was in an era of lunacy and super growth funds and our market share started to tumble greatly. The business needed to be saved. I did a really stupid merger. I said, “If you think American AOL and Time Warner was stupid I beat them.” If you know the kid’s game rock, cutters, paper, I was the rock and merged with a firm that was paper, a little advisory firm in Boston that had a hot go-go fund and who wanted to run the … I brought them in for their investment talent to run Wellington Fund to get us into the pension fund and give us that wanted product for the marketing side of the business called Ivest fund.

It went swimmingly for about six or seven years, the market collapsed. Ivest fund, the performance leader is it was going up. It was probably the worst performing fund in the industry in that decline in ’73, ’74 going down 65%. The other funds that my pals from Boston—these brilliant money managers—started, they were all going out of business now. They made no sense, I should have known better, I should have been fired . . . and I was. By the guys who ruined the performance of the funds because they got more votes in this merger than I did. Is this a great country or what? The industry had gone from a very good industry to a very bad industry and it’s actually a lot … we have elements of go-go, but mostly it’s become a giant marketing business. The marketing end of the business, always there, and triumphed over the management end.

You’ll see, even we have and I did this I think in a good way, but why do you have 270 mutual funds? Why do you have infidelities case 370 mutual funds? What good does that do the investor in the long run? I think the answer is not very much, if any. When you have to give them choices, for example if you want a bond fund, we may … Actually one of our innovations was to say, “You have to decide how much risk you want, principal risk, and how much income you want. You tell us whether you want a long term bond fund or a short term bond fund or intermediate term bond fund.” That’s the way the industry went, in that direction.

Today the industry is too much marketing and not enough management. Too much salesmanship, not enough stewardship and it’s been taken over in a lot of ways by giant financial conglomerates who bought into this growing industry. We now have owners of these mutual fund management companies. When they come in and buy a company for a billion dollars let’s say they’re going to take 300 million or 150 million out of that business every year, 15%. That’s their job. That’s modern capitalism. Where does that come from? It comes from the pockets of the mutual fund shareholders. Costs, believe it or not, from an industry that went two and a half billion in 1951 to 15 trillion today, the expenses are twice as high in ratio. I won’t try the math on what it is in dollars, but I guess it must be like 200 times as many dollars coming interesting the industry. Has it improved management? Are you kidding me? It’s just the same old thing. We’re all competing with each other. We’re all average before cost and below average after. Not a happy camper with the industry.

Speaker 1: When you started Vanguard you moved over from this pleasant experience. Did you have a vision of the kind of company you wanted and what would be successful and what would be competitive coming out of that learning experience?

(Watch on video starting at 15:43)

Question: Did you have a vision for the company you wanted Vanguard to become?

Jack: I think a vision would be a little bit lofty for the way I think honestly. I like the implied compliment, but actually you could argue it comes out of Princeton thesis. I don’t think it really did, which you can prove it, so I’ll try and prove it by the words that were in that thesis. I said things like … this is an idealistic college junior and then senior. I can’t shake the darn idealism even now, but even more idealism. I’m more idealistic now than then, which I don’t think is typical for most people. In my thesis I said things like the mutual fund industry’s principal task is to serve the shareholder, not the manager. I said, “Mutual funds should be operated in the most honest, efficient and economical way possible.” I have a sentence in my thesis that said, “Mutual funds can make no claim to superiority over the market averages,” kind of a hint about the index fund to come. Finally that the industry should be focused on management over all of its other duties rather than marketing.

It was predictive. I think that’s idealism speaking and not some genius kid who can build a company out of it, but it seems like in retrospect it is like in retrospect. That what I was saying there is what an industry has to do … everything I just said means we want to serve consumers. Adam Smith wrote in 1776 words to the effect, is the principal role of the producer is to serve the consumer. A proposition that’s so self-evident that I won’t even try and defend it. Always good to quote Adam Smith. I did have the idea that we would be the low cost provider. I did have the idea that if we were the low cost provider, that the index fund could come into its own and that low cost provider coming out of a mutual company. I have never owned Vanguard. That’s a unique structure in the industry. It’s owned by the fund shareholders. That’s where the economies come from. If you’ve got the structure your first question should be, “What’s the best strategy?” because strategy follows structure.

It just followed very logically. I did have a group of Stanford students that I couldn’t go lecture out there. I want to do in the worst way because I’m a lecture snob, but Palo Alto just too much for me, at least at the time. They said, “If you can’t come to the Palo Alto we’ll come to Philadelphia.” A whole bunch of them showed up in the office one morning. They asked me a bunch of simple questions, but my favorite one was, I had a little slide presentation. I said, “Our first business plan.” No bullet points, a blank page. We never had a business plan. Our business plan was to get through the day. This company, 1.4 billion down from 2.4 billion or 2.2 billion I guess in the market, in the fund performance that had been so bad. Everybody was so liquidating. It was going nowhere backward. We had to make it up as we went along.

We did were blessed however with a chief executive and founder who was a tyrant. A tyrant. There was no question who was running the company. It was a little bit capricious and arbitrary to say the least. Most of the things we did, I’m sorry to say, I’m embarrassed by this because it sounds so damn egotistical, but I decided. I didn’t talk to anybody about it. I didn’t see anybody around who’d studied more than I had. We just did these things one step at a time, the index fund, the new form of bond funds. We had been distributed by broker dealers all over the country. After a big fight with the board directors of the funds we eliminated all sales commissions and an entire distribution force overnight. I had a busy time on the phone that day.

It’s a product of I think some common sense, a lot of luck, but a timely thing because most funds are created to make more money for the managers. People bring out a hedge fund, they think they can make money. They really can’t, they know that, but the managers always do very well. In this industry the managers who sold to these conglomerates so I mentioned, do very well for themselves. That’s the way you get rich in this business, sell your company, but ours is not for sale because it doesn’t really exist. It’s owned by the funds themselves. It’s a little bit of a long answer. I’d love to say I had this vision from the beginning and just executed it right out of my mind, but that would be false.

Speaker 1: You maybe answered the next question I was thinking of giving to you, but maybe you want to add to it a little bit. When you started out with zero assets in your fund, Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, others were really light years ahead of you. As we sit here today and we’ve heard these, a couple of these statistics would go on the introduction, three trillion with a T under management, some 170 mutual funds, but we know that size is not everything in business and we see examples of that every day. I look at Morningstar rates you at number one, and that small company up in Boston number six.

Jack: They’re being generous. I shouldn’t have said that. Mike, I’m sorry, don’t write this down.

Speaker 1: I know. Is there anything else that you haven’t touched on as you look back and reflect that really not only started that momentum, but kept that momentum going all these years?

(Watch on video starting at 21:41)

Question: How did you grow larger than Fidelity and T. Rowe Price, who were light years ahead of you when Vanguard started?

Jack: It’s basically low cost, indexing turned out to be an idea whose time had come because in this costly industry, if you can be the low cost provider, since we’re all equal as managers, the active managers have to be equal. They’re buying from each other. I’ll let you in on a little secret, every time someone buys general motors somebody else is selling it. It is trading with one another and that’s a way to enrich some brokers and enrich the managers with their management fees. It’s a very flawed industry in terms of cost. The portfolio turnover for example. The index fund we can run for about five basis points, 0.05, just a little drop in the bucket. The typical active fund runs for about, let me say somewhere between 1% and 1.3%. It’s just a fraction of the cost. The investor is given an extra 1% or so on that basis alone.

Further, on index, you buy the Standard and Poor’s weighted by its market capitalization, meaning the largest stocks or the most important in the portfolio and then the index both. You don’t buy and sell anything because the index is the index. It goes up and your fund goes up and the market goes up or down. It’s right in accordance with that. We have zero, probably 2% portfolio turnover on our index fund. That’s expensive, not so much for us because we’re not trying to guess at things or push the market. The industry has about 140% turnover, portfolio turnover. That’s a hidden cost that people, everybody knows what it is by the way, all these people that we compete with. They say, “I don’t know what that cost is.” Come on, if you don’t know what that cost is, go get in a business which you know about. That’s another three quarters of 1% cost advantage and then we have no loads as I told you, abandoned the sales charge. Some of that’s probably another 50 or 70 basis points on average that’s spread over time.

We have this huge cost advantage and that’s where everything else come from. When you’re promoting you don’t have a hot fund to promote. You have a market, we’re a guarantee that you’re going to get your fair share of the market’s return, whether it is good or whether it is bad, I keep reminding people. That’s all we guarantee and yes, people will move ahead of us, but then they’ll move behind us. Everything reverts to the mean, becomes average and below because of cost. It’s a pretty simple concept and the competitors hate it. When I brought out the index fund in 1976 it was underwritten, there was a big poster being passed around Wall Street. It showed Uncle Sam with a great big cancellation stamp and with a field of stock certificates around him. He was going boom, boom, cancel, cancel stock certificate. Stamp out index funds. Index funds are un-American. I had it right outside my office. It was not popular. It took us a long time to get some momentum, maybe really end of the … in the late ’80s or early ’90s. It was a real fight. Everything we did was a fight, a battle over the competition. A battle to get our message across. This may have occurred to some of you perceptive people in the audience. I love a fight.

Speaker 1: I felt that there is something about Vanguard and I’m sure people in this room have come to the same conclusion, that you haven’t touched on, it’s contributed to success and is not easy and it can only be achieved when it starts at the top. What I’m talking about is … Before I get to it I will lead up by saying Vanguard seems to many of us to be the only shareholder cooperative out there dedicated to customer service. I want to talk about customer service. Of course, to being the low cost provider, but that’s still about customer service. In a sense Vanguard is perceived by many people as us, the investors. Those of us, and it probably speaks for everybody in this room whose careers have been in corporate business and know the importance of getting a customer service coacher is extremely difficult to get going and extremely difficult to keep it going, recognize the importance of it. A lot of people give it lip service, but not a lot of people achieve it to the level they wanted to. You’ve done it for 40 years. How’d you do it?

(Watch on video starting at 26:29)

Question: Lots give customer service lip service. How did you achieve a very high level of customer service at Vanguard?

Jack: It’s really quite an easy answer to that. I give a damn about people. I’ve often used the phrase, let’s never forget the honest to god down to earth human beings. We’re trying to find a way to achieve their financial goals. I believe it in running a company. I spend much more time than any chief executive I’ve ever seen mingling, mixing, working with, rolling up my sleeves with the people that are doing all the hard work. They know they have respect. They know they’re going to see me in our little galley up there. We do not have a, “Oh, this will surprise you.” We do not have an executive dining room. I can’t imagine anything worse for a company, honestly, a company like ours. Certainly I shouldn’t criticize anybody else, but there was just never any question of doing that kind of thing. I’d get on the phones in the old days, and I’m not smart enough to do it anymore, and answer shareholder calls and the people around me saw that. I’m still very close to them. They know that I’m going to be in that galley every day that I’m there with … I guess it holds 300 or 400 people, I don’t know. We’re so far spread out that you can’t do as much as you’d like.

They know I’m going to be there and they know when I am there and when I’m not there. One of our crew members, a lovely woman just I guess two days ago came out to me and she said, she had a friend that didn’t believe I ate in the galley. She’d taken a picture of me eating there. I said, “That would be just fun.” Then she said to her friend, she didn’t do a selfie, I’ve had a lot of them. It’s amazing the amount of spirit, the people we have in this big company. I think keeping those values when a company grows from 28 people, which we had at the start, to I guess we have about 16,000 crew members now as we call them. I didn’t like calling somebody an employee. I think it’s demeaning and out of character. We use a lot of nautical metaphors there. When my wife heard that a new exercise area that goes off our galley was called the Ship Shape Room, she said to me, “Don’t you think you’re going to run out of nautical metaphors?” I said, “I don’t think so.” I keep going on. Vanguard of course was Nelson’s flagship at the great battle of Nile in 1798.

Three trillion dollars means nothing to me. I’d rather complain about it than brag about it. It wasn’t so long ago, probably about a year and a half ago, when someone stood up in a Q&A that I was doing and said, “You must be very proud to have crossed the two trillion dollar mark, growing quite rapidly.” I said to him, “Look, what do you think two trillion dollars means to someone who has written a book called Enough?” I just was never in it for the size. I was in it for the fun, for the battle, for trying to keep people around me on the same level that I was. I was an autocrat. Please don’t mistake that. I was worse than the tzar, Genghis Khan, I don’t know, you name him. We have a wonderful kernel of personal respect and affection. I can guarantee that throughout the lower levels of Vanguard, a real identification with … I talk a lot. I used to have speeches every anniversary, every billion dollars we grew. It goes to seven, to eight billion, imagine that today. I’d be talking all day long if I was still running the company.

Every time we’d have a billion dollars crossing, it goes from seven to eight billion, we had a party. That was a big deal. At ten we went to I guess ten, 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, it’s all whatever it is. Instead of being, not very many years ago, 200 billion dollars behind Fidelity now we are 1.2 trillion ahead of them in assets. That said, I hate to say this, because he owns his company, I don’t own mine, Ned Johnson is worth more than I am. He happens to be worth 26 billion, he and his family, which is a living. Or at least I should say I understand it’s a living. I won’t take it for granted, I wouldn’t want that.

Speaker 1: Jack, going from 28 employees to 16,000 you said, obviously you had to put in place over these 40 years and develop and grow a management structure, a team and all. Not easy. Did you do it primarily from within, some from without, a combination? What was the secret of doing that because that’s a real challenge?

(Watch on video starting at 31:40)

Question: What was the secret to grow from 28 employees to 16,000?

Jack: It’s all from without because there’s only so much you can do from within when you’ve got 28 crew members. I was not particularly good about that. I don’t consider myself much of a management person. I don’t think I’m much of an executive. I talk about the value of team work often and I don’t have a lot of that in me. Sorry to say. You probably can sense all this, and I don’t know why I’m revealing the inner Bogle here. I cover over stuff, that’s true. We had some good people that were much better at organization than I would ever be. All the things that had to do with computers and half of those 16,000 crew members we have now are in technology. In terms of investment this is an interesting point. We probably have maybe, let me say 300 people out of that 16,000 working on investing and funds because indexing doesn’t require that much. It requires a lot of stocks and companies’ stocks split and all that. People have to do things, not very much in that space, but all that work has to be done, but it’s not investing and saying, “I think this stock is better than that stock.”

We had a vaguely managed mutual fund, they’re called managed funds. I don’t call them managed funds, our municipal bond funds. There isn’t a good municipal bond index. I’ve had to create municipal bond funds that were so index like that they have a correlation with probably 100, a perfect correlation with their share of the total municipal bond market. It’s a simple business from an investment point. The big test, we really have … this is going to sound bragging. I don’t think it is really, but there are two sides to this business, any business and it is really in response to your question, which is really so good. There’s the investment side, there’s not much we can do wrong. We’re going to give you the market return. Every once in a while the funds will do better. Last year happened to be a particularly good year for the S&P 500. Just sometimes it’s particularly good and sometimes not particularly good because there are so many different concept funds out there.

That—we have a lock on that. We will deliver on the promise. If you pick an index fund that’s in emerging markets you will get that return. We have that and we have a few actively managed funds, some of which have done well and some of which have done okay. That part of the business really under pretty good control. The whole other side is the human side of business. If you don’t have people who are committed, dedicated and enjoy coming to work you have a real problem. It counts how you feel about your job. I feel profoundly about this and I ask people. I spend an hour with each of our award for excellence, we have that kind of award program. I spend an hour with each one still, but I guess there are about 12 a quarter, something like that. I never asked the question directly, but I can tell you they all say there are two reasons they, these are not high level people, two reasons they stay at Vanguard.

We do have good benefit plans, competitive salaries and then the partnership plan that I created where they share in the savings that we generate for shareholders. They have a nice package, not hugely generous, but probably figured out, 30% of their … usually it was when I was running it, 30% of what you automatically in June got an extra bonus topped out of 30% of your income. You got great retirement plan, great benefits, competitive salaries and then throw in the partnership. It’s a good living, it’s not sensational. We have that going for us, but the two reasons I get, sometimes one two, sometimes two one, I really like working for a company that has a sense of values, a company that has a sense of doing the right thing, a company that has something resembling integrity. A company dedicated to service. A company who knows who their clients are and we’re dedicated to serving them is one, call it the Vanguard environment. The other is, very frequently and very strongly, maybe even stronger, I really love the people I work with.

You can’t do any, I don’t think, I wouldn’t know how to do better than that. If you can get that kind of a feeling, that kind of a commitment, there are a lot of routine jobs that go on here. I did them partly because I was capable of doing them unlike many of the non-routine jobs that are there. It’s just a pleasure to be around them all. As we get big I have a saying, give a few business people in the audience a little, I think, a good tenet or motto, I have a speech I gave in 1995 talking about the perils of coming growth. You can see it all coming, it didn’t take a genius. Take your growth rate and cut it in half and extend it for 20 years and you get to three trillion dollars or at least two. For god’s sake, I wrote one of these speeches to the crew, for god’s sake let’s always keep a Vanguard at place where judgment has at least a fighting chance to triumph over process. I got bad news for you. The bigger you get, this is process, this is judgment. You said it just right, exactly right. Size is now a mixed blessing.

Speaker 1: I’d like to shift a little bit and something that’s been in the papers for a long while, but certainly the last couple of years and the last 12 months particularly. That’s what seems to be the phrase activist investors, activist shareholders. I understand there a couple of questions here are rolled together and let you attack them. I understand that Vanguard and some of its peers are considering joining the growing shareholder activist effort that is underway by shareholders to try to initially address corporate governance issues. We’ve seen those issues develop and change. Five, six, seven years ago it was trying to get a lead director. It was trying to have more … this was all really done through proxies. You’ve all probably recently been filling out your proxies in the last month or so for the annual meetings that are going on. It was issues like trying to vote out change of control provisions where existing management was helping themselves along those lines or maybe overview of executive salaries. Now that’s still going on and they’re looking for more disclosures about lobbying fees and all that stuff. Now it’s moved to where smaller investors, institutional investors, hedge funds, is trying to come in and make changes in companies like they were a private equity company and they were going to buy the whole company and then they were going to do it for better or for worse.

Jack: And leverage to the skies.

Speaker 1: And leverage themselves to the skies. Now they’re coming in and buying maybe 1% or 2% of the company, calling for the CEO to be fired and they’re all doing this form the outside, not from any inside information, and calling for, you ought to split this company in half and sell off this division and that division. I don’t understand the synergy of why you have those two different complementary operations. It concerns me and I worry and I think back to my days when I was working for a living and was seeing some of our customers under pressure from the analyst community, that they were really only interested in the next quarter earnings which are often forecast by three or four 26 year olds who’ve never had a real job in their life.

Jack: They’re only 24.

Speaker 1: They’re only 24. They’re not interested in the long term financial health of the company. They’re just looking to pop it. I’ve wandered on here, but it’s a topic that’s getting a lot of attention.

(Watch on video starting at 40:01)

Question: Any thoughts about activist shareholders hurting long-term investors?

Jack: You’re certainly wandering along the right road. What’s happened is we have a situation that has never prevailed in the history of corporate America. That is we’ve had for as long as we’ve had public companies an agency problem or the leaders of that company representing themselves or the shareholders. Executive compensation is a good example, doing a merger to say you’re bigger than the other guys another example. Doing a merger so you can muddy the books and play with the accounting games is another example. It’s not a happy situation to have developed that way. That’s an agency system that Burley and Means if you’re an academic wrote about in 1935 or 1936, about the problems, management. The book was called something like … I read it at Princeton so I can’t remember the exact title, in 1950 or ’49 I guess. It’s separation from management and ownership. That’s always a problem.

Now we have another agency. We have the mutual fund industry owning 37%, the largest stock holder in America. The managers of the mutual funds are agents for the mutual funds confronting the executives who are the agents for the corporation shareholders. It doesn’t seem to work very well. When you go beyond just the mutual fund industry we’re all, us, Vanguard in a smaller way than most, but still there, partly in the pension business, defined benefits business, and certainly in the defined contribution business which we’re the most dominant industry by far. We have probably 55% or 60%. We control, this group of institutional investors, control 55% of all the stock in America. Vanguard alone controls 5% of all the stock in America. Black Rock has I think the other 5% and then you go down from there a little bit.

But we don’t vote actively. The SEC had proposals a few years ago saying, “Here are some ways you can get access as it’s called in a proxy, nominate directors, vote on things.” Nobody asked for … not only nobody asked for more access. It was limited, but nobody even wrote among our competitors, this big issue of the SEC. None of the mutual fund companies wrote a thing. Of course, I guess it’s not … I’ll say it anyway. I was not running Vanguard at that time. We have to take a more active role. One of the problems is that we are running, in our defined contribution plans and defined benefit plans, savings plans and the pension plans, we are running the money of the companies in our portfolio. I could never find out who said this, but I recently came to the conclusion it was me. That is there are only two kinds of clients we don’t want to offend in this business, actual and potential. Correct me if I’m wrong here, but I think that’s everybody because if you offend A, B is not going to give you his business.

Everybody tells me that’s overdone and people have even told me it didn’t exist, which I can’t accept it doesn’t exist, but maybe I’ve over-weighting it. I think we should, actually some years ago, beginning of 2002, I tried to get together a bunch of mutual fund investors, I wasn’t even running Vanguard then, tried to get together a bunch of mutual fund and pension investors to form a federation of long term investors. People would vote for their shareholders looking at the long term, not the recent earnings and all that stuff of the company. We had a nice meeting in New York. Somebody else bought the lunch. There were probably a dozen of us there and two or three people who wanted to be a part of it, but didn’t dare be associated with it. That’s how sensitive this issue is. At the end of the meeting the chairman of one of our competitors looked up at me and said, “Jack, I understand what you’re trying to do here, but why don’t we leave it to Adam Smith’s invisible hand?” I said, “For god’s sake, don’t you know we are Adam Smith’s invisible hand?”

Everybody’s going to take of course a lot of money. It is not relative to the size of this multi trillion dollar business. The idea was to get together and look at companies as a group and not tell anybody how to vote, but just to analyze it from the standpoint of the shareholder. Benjamin Graham wrote at length about this, much tougher than I ever did and ever even thought, but something has to be done to give the stockholders of American corporation, that the stockholders of American corporations now are almost entirely institutions in this, what I call, the double agency society. This agent facing that one. Someone’s got to make sure those corporations are run for the benefit of their shareholders.

I don’t think we in this business, most of which aren’t particularly well run by the way, should tell corporations how to run themselves. I don’t think we know how. I don’t think we should make a lot of noise about it. Just make sure the corporation is being run in the interest of shareholders, taken on on political contributions, taken on on executive compensation, taken on on mergers. Try and work on short termism by saying you get a premium dividend if you’ve held the stock for more than three years say and be able to combine to vote if you’ve held the stock for three years and altogether on-board own say 5% to 10% of the company. It’s moving in that direction, it will, but it’s going to be a long tough struggle.

Speaker 1: I have one more quick question, another type of concern that I think the average investor and then we’ll throw it over open to questions here because I know there’s a lot of them. I’d be interested in your thoughts if you think regarding the need for some types of new regulations or controls to protect what I would call the average investor. I don’t mean to protect them from making a wise investment decision or a poor one, but in this era that we live of electronic high speed trading, the tremendous volatility that we have in the market, so much of it being caused by organizations that have enormous amount of assets, but they’re buying stocks in the morning, they’re closing out their books and all their positions at 4:30 in the afternoon.

Their decisions are all based on mathematical algorithms. They really don’t give a damn about how the company is doing or what’s happening. Was it up an eighth, down an eighth, should we buy, should we sell. I think this has turned off, we read it all the time. Is this concerning and unsettling to a lot of the average investors? I’m sure frankly some of that might be why they’re into your index funds. Does something have to be done to try to return and bring back what I would call the average investing market from what’s now … Many a people today I think feel that the market is just merely a provider of almost a technical trading platform. It has nothing to do with the typical investors. That’s a mouthful for me, but …

(Watch on video starting at 47:58)

Question: Are you concerned about how the market is changing with high-speed trading?

Jack: First there’s a lot in what you say. I’m not happy with it either. I guess the one thing I’d say is it shouldn’t bother anybody in the room, any stockholder when he’s investing for the long term, investing for retirement and just trying to put his or her money to work satisfactory, that these jumpy markets simply do not matter. They are funny, they do it for no reason at all. The press will get us an explanation to why they went up and why they went down without any knowledge. They’re basically saying, they went up, there must be some reason. No, there’s no reason. Just a little speculative wave going through there. It basically, I think with the first responsibility we all have is not to really care about that. No mutual fund shareholder is damaged by the fact that the stock market goes up and down. You want to buy or sell during the day, I don’t know why anybody would do that and I’ll come to a little variation on that in a second. It doesn’t affect you unless you’re actually part of the pricing.

The trick is, and we’re starting to make a little progress. You may have read about it in the papers. We’re trying to get this business to turn more toward being a fiduciary business than the marketing and the salesmanship business. I actually had the privilege of working with the people of the department of labor, the national economic council and the council of economic advisors to try to get this fiduciary duty standard applied to retirement plans by the labor department. Of course, the SEC is complaining because it’s their turf, but the department of labor is saying, “Well wait a minute. You’re not going to do anything.” We’re trying to save retirement plan investors to get exactly where you are. People should realize that activity is costly. The less active you are the better you do. That’s documented or common sense. I shouldn’t say documented, but you know it in your common sense, what is documented in the data.

It doesn’t bother me much. We cannot turn our back on speed. You’ve got to put a light to it whether it’s speed of the information age, speed of the stock market. I wrote an op-ed about this subject for the journal portfolio management company. I began with the first speedy trading and maybe even inside information. When Werner Rothschild heard about the duke of Wellington’s victory at the battle of Waterloo and sent carrier pigeons to London to tell his people to buy, that the British Empire was in danger, in peril. All of a sudden they win this great battle of Waterloo under the duke of Wellington, the name of my previous company. That’s the first indication of speed coming into the market. It’s hard for me to see it can go a lot further, but it’s now … the activity in the market is absurd. The interesting part of this and the deeply disappointing part of this to me is that indexing has become the new speculative way through these exchange traded funds. They’re traded all day long. The original slogan was, “Now you can trade the Standard and Poor’s 500 index all day long in real time.” What kind of idiot would want to do that? I just can’t imagine it.

Every day work on the Wall Street Journal, sometimes you’re going to do a little math, but not usually. The most actively traded stock on the New York stock exchange is the SPIRE, that Standard and Poor’s 500 exchange traded fund. It trends around 20 billion dollars a day. That’s an annual turnover of I think it comes out to about 2,700% per year. 2,700% turnover. It doesn’t matter to me and actually the inventor of that fund, if I can tell a little anecdote here. I don’t want to waste all of your time, but he came to me, Nate Most, Nathan Most, and he said, “I’ve got a great deal for you,” in my office down at Valley Forge when I was running Vanguard. He said, “I have a way that you can trade your S&P 500 and we use it. You can get much bigger because you can get all the traders,” and I said, “Look, that’s just not my bag. We’re not going to do that.” It’s now a hugely successful fund, run by State Street. Ask me if I care. I just am not a trader. It’s long term investing, it’s fiduciary duty what we’re working on in Washington. People are figuring out a way that brokers aren’t … where they don’t have to say, “I’m putting your interest first.”

Why anyone in the financial business who touches other people’s money wouldn’t want to say their interest comes first I don’t know. But we’re moving towards something I’ve been in favor of. Maybe this is a good way to end the portion, something I’ve been working for you could say since 1951. That is to have funds run in the interest of the long term shareholders and have a fiduciary duty to those shareholders as a federal standard. We’re creeping up on it through the labor department right now. I won’t see it come to its full fruition, but I’m very happy with the direction we’re going and I’m really happy to be part of it.

Speaker 1: Why don’t we stop there, Jack, that’s terrific. We’ll start with questions. Judy’s over on this side. Judy’s got the microphone, why don’t we start right here. I’ll just reiterate Phil’s comment. I can see there are many questions. We have maybe 25 minutes or so. Tokes, no essays. You get two questions as long as they’re not separated by an essay.

Speaker 2: Two questions, you’re welcome to comment on either one or both. One, given the cap weighting of the 500 index tell us something about smart beta funds and number two, your opinion on the consumer financial protection agency.

Jack: Number one. The cap weighted versus smart beta.

Speaker 1: You might have to explain that to make sure we’re …

(Watch on video starting at 54:14)

Question: How do capitalization-weighted mutual funds compare with “smart beta” funds?

Jack: Smart beta is the new buzz word in the mutual fund industry. Smart beta is if you will … Let me say, I don’t like new products. I don’t like hot products. I don’t like products. Mutual funds shouldn’t be considered products. I don’t like new products, new, and I don’t like hot. You can imagine what I think about hot new products. It makes no logical sense. It makes no mathematical sense. There’s no such thing as smart beta. If there is there’s got to be a dumb beta because we’re all average in the long run. You’ll have to tell me that you can pick out the smart beta and the dumb beta. It just makes no sense at all. We’re relying on my own feeling about it, which I just hate these buzz words. It’s a simple business, why mess it up. William Sharpe, Nobel oriented economics, one of the great thinkers of American investing, worldwide investing for that matter, says, and I’m quoting directly here, “Smart beta makes me sick.” I would never say that myself of course. The second one was?

Speaker 2: The second one, would you say something about the consumer financial protection agency?

(Watch on video starting at 55:36)

Question: How do you feel about the consumer financial protection agency?

Jack: The organization, the government? Consumer financial came on after huge disputes in congress and I think was appointed when the congress was out of session, they were still fighting about that. I do not believe in big government, but I believe that the financial industry generally, consumers, credit, mutual funds even has unfortunately earned government oversight. It’s like there’s no problem there, the government doesn’t need to do anything, but there is a problem there. There’s a disclosure problem and information problem and overcharging of interest rates on the consumer side mainly and the mutual fund industry has its own set of problems. It’s marketing these new funds and overcharging and all that. I don’t like it, but we need it, so we have to have it.

Speaker 1: Any other questions on this side or we’ll come back, we have one right over here Judy.

Speaker 3: Thank you very much for coming out this evening, bringing so many years of successful experience. We really appreciate it. Your prediction on inflation, where are we going to go on inflation.

Jack: It’s a great question.

Speaker 3: I’ve got another one, please.

(Watch on video starting at 56:56)

Question: What is your prediction on inflation, and what investors should do about inflation?

Jack: That’s alright. First we’re going to stay I believe at low inflation levels for longer than the federal reserve keeps this very tight money policy. I think that’s because we don’t have a great big underlying consumer demand in this country. Consumers are still somewhat extended. Corporations are not particularly extended and trying to de-leverage as they say. Money is going to have to go to de-leveraging, but when you’re talking about these kinds of things the consumer’s obviously what you’re asking about. I think that we ought to be able to stay in this range of say 1% to 2% for a fair amount of time. I don’t know any better than Janet Yellen does whether that’s going to be a long time or a short time, but at the end we’d probably be walking along with a more traditional 3% inflation. I don’t see it getting out of hand and out of control.

The inflation bond, we have, as many of you probably know, you can buy a ten year treasury note or bond, short term bond, ten years and it will yield you about 2% today. But you can also buy one that has an inflation hedge in it. If inflation goes to 4% you’d get more money than the fellow that doesn’t have that protection. It’s about 2% and the inflation bond is selling at about zero, maybe even negative. The market is saying and the market is not always stupid. The market is saying, “Be pretty relaxed for as much as ten years.” I wouldn’t be relaxed about anything out there for ten years. The world has too many uncertainties. I don’t see a big wave of inflation like we had after, for example, world war two.

Speaker 3: Second, with an 18 trillion dollar deficit and it’s increasing approximately a trillion dollars each year, how are we going to handle this and can we handle it?

(Watch on video starting at 58:48)

Question: How can we handle our 18 trillion dollar deficit increasing a trillion dollars each year?

Jack: I usually talk about social security deficit, but that’s an easy one to solve, social security. The only way you can do it at the federal level is raise expenditures or reduce revenues. These deficit problems are very easy to conceptualize. Will we grow out of it over time as we get some better economic growth? That can help. Can there be things done to cut back government? The answer is it’s herculean to cut back government. I can’t give you the exact number, but if you take the things the government cannot cut back on or will not, we’ll argue good or bad on this, like military, like social security commitments, like paying the interest on the federal debt, which is quite large enough thank you and that will probably go up as interest rates will go up. It will go up and federal debt is not particularly long in its holdings up there. You’re working with a very small portion of the total budget when you try and cut there.

You can raise taxes, of course. I’m in the group that … normally I guess I’m deep down somewhere between a communist, a socialist and a Marxist, but I believe that we have an obligation in this country to take the best care we can of those who aren’t as privileged as all of us in this room tonight. I don’t mind paying my share of that. Unfortunately the amount of waste there is enormous, but when you get federal programs that apply to hundreds of millions of people it’s going to have some waste in it. I’m sure that can be improved on, but that’s not going to solve the problem. I don’t think you can really raise taxes a lot because the top 10% of the tax payers are probably paying, let me just guess, it’s 75% of the total tax burden, but it’s totally disproportionate. I think someone else would be better on this than I am, but around 40% or 50% of the quote tax payers in the country pay no tax at all. They’re down to very low earnings. They’re paying social security taxes, which is at 6% or 7% is a big hunk of their compensation. 20,000 dollars a year or whatever it is. It’s pretty low.

I think the best possible approach is to try and do things that are more efficient in the way we tax. I think it’s ridiculous … I feel anyway, I’m going to say it and I’ll surprise you. It’s ridiculous that hedge fund managers can take their earned income and pay a capital gains rate on that. [Clapping] Oh! Alright! I thought that people would disagree with me. I think that it’s ridiculous that we let mortgage rates be unlimited. The whole idea is to make sure that people are able to afford houses, but if you get to let me just pick a number out of the air, 200,000 dollars, that would be the limit on any mortgage I would allow. Those people maybe need the help a little more. There’s no way to get equity. As anybody will tell you correctly that if you have capitalism you have inequity.

There’s no way around that, whether it should be this extreme I am deeply concerned about the inequity in our society, the spread between the top 1% and the bottom probably 50%. Actually I have a file, Mike knows about this, in the office with data on this inequity where articles and things like that come up. The file is entitled America. I just don’t think it’s right. I wish I could solve it, but I think it’s not at all hopeless. If we don’t grow we have a real problem on our hands, but the growth will help. Some intelligent elimination of tax advantages will help and maybe some tax increases, different kinds of tax increases. People talk about a value added tax. They’re all still taxes, but it’s a very problematic, to say the least, problem. I wish I could have enlightened you as to how to fix it, but Mike is going to do that tomorrow.

Speaker 1: I see one in the back.

Speaker 4: This was quite enlightening, thank you. I had the good fortune and a quite stimulating experience to work with or study from William Sharpe at Stanford, great guy. My question to you is the following, this 2% of return that someone might realize on a Vanguard investment, a 0% real return if you go with Fidelity or T. Rowe Price. Is it possible to know something about these markets with hindsight to determine whether investing in specific developing economies given their macroeconomic profiles in specific sectors in particular risky categories of equity based on their correlation with market ups and downs and the little bit that’s left over when you take those correlations out, is it possible to make better decisions about where you put your money? I’m sure Vanguard has products that address these issues. Can you give us any suggestions about where a good place to be if you’re 70 something and contemplating maybe two or three more years of productive life you might want to put your money?

(Watch on video starting at 1:04:53)

Question: Is it possible to make better investment decisions based on long-term analysis of specific sectors in stock market?

Jack: My first thought is I want to be 70 again. I think that the risk of investing, let’s say the risk of owning the stock market is quite large enough. The stock market is the stock market, it does what it will. Trying to go beyond that risk by taking greater risk, somebody else is going to be taking lesser risk obviously because it’s all a closed circle, I think it’s very unwise to take an extra market risk to buy individual stocks, to buy individual groups of stocks, to buy sectors which are traded a lot in these exchange traded funds. I don’t think the traders do very well. There’s some problems that trying to get around them is going to be more expensive than trying to stay with them no matter how limited the returns are. I would not do it. You talk about … there’s a lot of talk about and I get a lot of trouble in this when I speak out on it, but I’m saying the same thing like I have with everything for about 35 years, maybe 50, maybe 64.

You have to realize that it’s a zero sum game for all of us together. If you’re, as I said about the beta thing, if you’re the smart beta there’s got to be a dumb beta there, but I do get in a little trouble about what you specifically asked about and that is non-US stocks. I just don’t believe that countries out of the US, I think this is a great country to invest in. We have the best technology, we have the best national growth, not compared to China and India and so on, but of the established countries. We’re doing much better than the European countries about the size of the US together after the recent unpleasantness back there in 2008 the financial crisis. These US corporations receive half of their revenues and gain half of their earnings outside the US. You’re betting that the foreign markets will display that differently.

[Russia (?)] by the way, very importantly, as long as you don’t have it … when you don’t have it you know what you’ve missed, but we also have the most established shareholder protections in the world. You can be confident that the institutions we have built up in this country are giving the owners of stocks, the owners of anything for that matter, greater protection than probably anybody in the world. Maybe not England, but right up there. I just don’t see the value in doing it. I know I am not smart enough to do it, but if you think you know more than the market, be my guest. I don’t like the extra risk. I don’t like the concentration. I’m willing to take America’s businesses’ return and whatever returns the bond market offering and not even … The good rule of investing, never peek, never peek. That’s P-E-E-K.

Speaker 1: Jack, thank you very much. I think we’ve been a stimulating hour plus. We appreciate your comments, we appreciate the effort you did to come down here and share your wisdom. You can see you had a rapt audience. I don’t know if they’re going home feeling better about their portfolio or not.

Jack: I can only say the facts.

Speaker 1: I think once the Buffet factor is over with your books I think the Aspen factor will move in here. In any case, we just very much appreciate what you’ve done for us.

Jack: Thank you. Thank you.

Footnotes and Credits

This video was produced by The Aspen Institute and published on YouTube Apr 21, 2015 on their YouTube channel The Aspen Institute. Their videos are excellent. They produce them and own the copyright. They have given me permission to embed this via YouTube license onto this educational website.