{Editor: retirement income is a specific instance of financial planning, but one that should be a high priority goal for everybody. Investing for retirement suffers from some pervasive misunderstandings which cause investors to carry unnecessary risk or sacrifice happiness (less leisure or less spending).

Professor Zvi Bodie has been one of the most vocal champions of fixing the broken, and taking advantage of products beyond stocks and bonds to enjoy a better retirement. His contributions help ordinary investors manage risk.

The following is an eye-opening look at the traditional methods of investing for retirement and a new paradigm using what economists call Life-Cycle Finance. It’s an easy-to-understand presentation and I share it here with Professor Bodie’s permission. Zvi Bodie is also famous as an enthusiastic supporter of iBonds and TIPS bonds which he touches on at the end. This presentation is facilitated by Austin S. Rosenthal, Vice President, Dimensional Fund Advisors.)

Retirement Income Planning

>>AUSTIN: It’s my privilege today to be able to introduce a good friend of mine, a former colleague and professor emeritus of Boston university and president of Bodie Associates, Professor Zvi Bodie. Thank you for being here Zvi.

>>ZVI: My pleasure, Austin.

>>AUSTIN: So, in today’s session, we’re going to review first of all, what is Life-cycle Finance Theory so we can all get a tutorial on that, and then how you can use it in financial planning, not only for defined contribution plans but also really for retirement income planning. So we have a packed agenda. Now we get to go back to school and learn about life-cycle finance. Professor Bodie, the floor is yours.

And maybe before I get you going, I wanted to ask you, where does life-cycle finance even come from?

>>ZVI: All right, I’m glad you started with that question, Austin, because it gives me the opportunity to say something about the history of the subject matter of the life-cycle. In economics literature and there is a voluminous literature in economics, several Nobel prizes have been given for work on the theory of life-cycle consumption. Most notably Franco Modigliani, Milton Friedman. And that theory is central to all of economics because economics is really about a theory of how society runs with consumer sovereignty. Consumers are at the central, at the center of economic theory.

What is life-cycle finance?

The life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) is an economic theory that pertains to the spending and saving habits of people over the course of a lifetime. It presumes that individuals plan their spending over their lifetimes, taking into account their future income. It addresses the common problem of maximizing happiness over what might be 30 years of working and saving followed by 30 years of spending—life with its abundance of unknowns.

Life Cycle Finance

The science of finance is all about the element of risk, and applying that science to improve our lives. Finance brings products and strategies to manage unknowns like: How long will I live? How much do I need to save? How much risk should I take with my investments?

Life Cycle Consumption

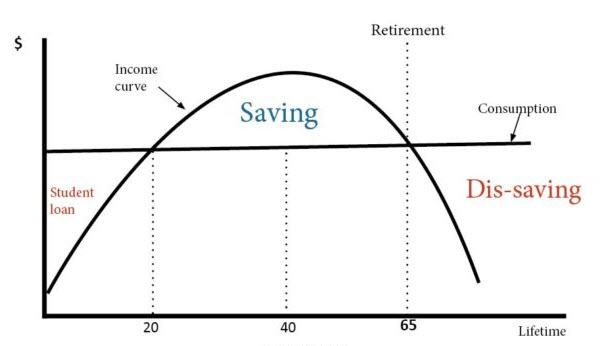

Consumption in this context includes both leisure (waking hours not working) and spending. Life-cycle consumption is the idea that individuals seek to smooth consumption over the course of a lifetime to maximize their happiness – borrowing in times of low-income and saving during periods of high-income.

The ideal of smoothing consumption is captured in this graphic by www.economicshelp.org and is an important aspect to maintaining your standard of living, and hence: maximizing lifetime happiness.

>>ZVI: The original work, which is still considered the classical theory of consumption over time, the allocation of economic resources over time is Irving Fisher’s work from the early 20th century, The Theory of Interest. In other words, how you can explain interest rates, equilibrium interest rates on the basis of consumer decisions, whether to consume today or tomorrow. They call it the rate of time preference, technical idea.

Anyhow, suffice it to say that all of that literature prior to the arrival of Robert C. Merton did a great job of explaining the time dimension of resource allocation. Terrible job of dealing with uncertainty, and really what makes finance a separate branch of economics, some would say it’s more than just the economics, but the science of finance is all about the element of risk. Yes, timing is very important as well, but it’s really risk and how you model that correctly.

…the science of finance is all about the element of risk.

Professor Zvi Bodie

So it starts with a pair of papers written as part of Bob Merton’s doctoral dissertation along with his thesis advisor, Paul Samuelson back in 1969. Both of the papers which were published in the same journal the same year are about life-cycle consumption and investment decisions, portfolio choice decisions. The element that Bob Merton brought to bear was a whole branch of mathematics, which had never been used before in economics. It’s called the Ito calculus, stochastic calculus in continuous time. He revolutionized the field.

>>AUSTIN: You guys have been working on this for 50 years now and let’s get into the slides. Here’s your clicker.

>>ZVI: Thank you.

Safety-first Retirement Income Planning

>>AUSTIN: You’ve been working on this for 50 years. What’s the problem? What are we trying to solve?

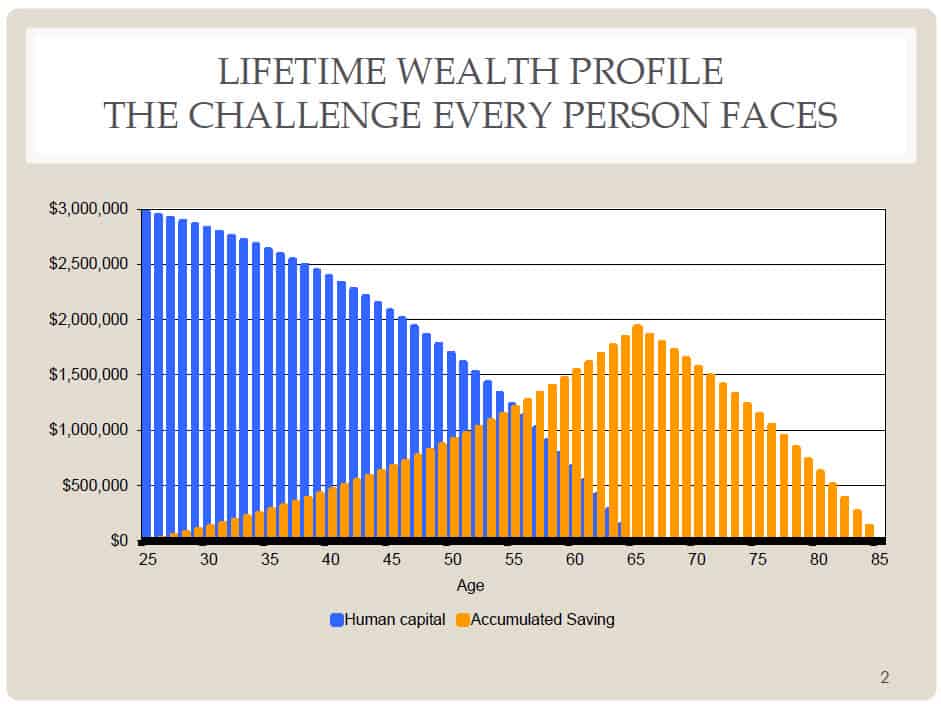

>>ZVI: So here is the picture. What is the basic resource that you have? It’s your earning power. And what we see in this diagram is the present value. This is age 25, this critical age here is 65, which we’re going to assume is the age of retirement, and 85 which is the age of expiration to put it in a subtle way. So that’s the lifespan. Earnings until age 65, saving during that period. So the orange curve represents the accumulated savings in presumably a retirement account.

>>Initially there’s nothing there at age 25. And this blue curve is the present value of all your future earnings. And in the model that Bob Merton and eventually I jointly developed, this is the present value of how much you can earn assuming that you work as much as you possibly can. So it’s 70 hour work weeks, 52 weeks during the year.

… two basic decisions you’re going to make, how much leisure to consume, including when to retire, and how much to consume. And the other decision is how much risk to take with your savings.

Professor Zvi Bodie

One of the decisions that you’re going to make over your working career is how much leisure to consume. So the life-cycle in this simplified model has two basic decisions you’re going to make, how much leisure to consume, including when to retire, and how much to consume. And the other decision is how much risk to take with your savings. And you have a certain amount of risk already in your human capital, and that’s a critical determinant.

What is human capital?

Human capital refers to our ability to do useful work in the future, work that others will value. Our knowledge, skills, creativity, habits, and social and personality attributes all form part of the human capital that contributes to the creation of goods and services.

Human capital is quantified as “a present value of lifetime potential earnings, assuming full-time work. The reason we define it that way is because the individual is going to choose to spend some of that on leisure. Now obviously, it’s not actual spending, it’s just not working two jobs.”

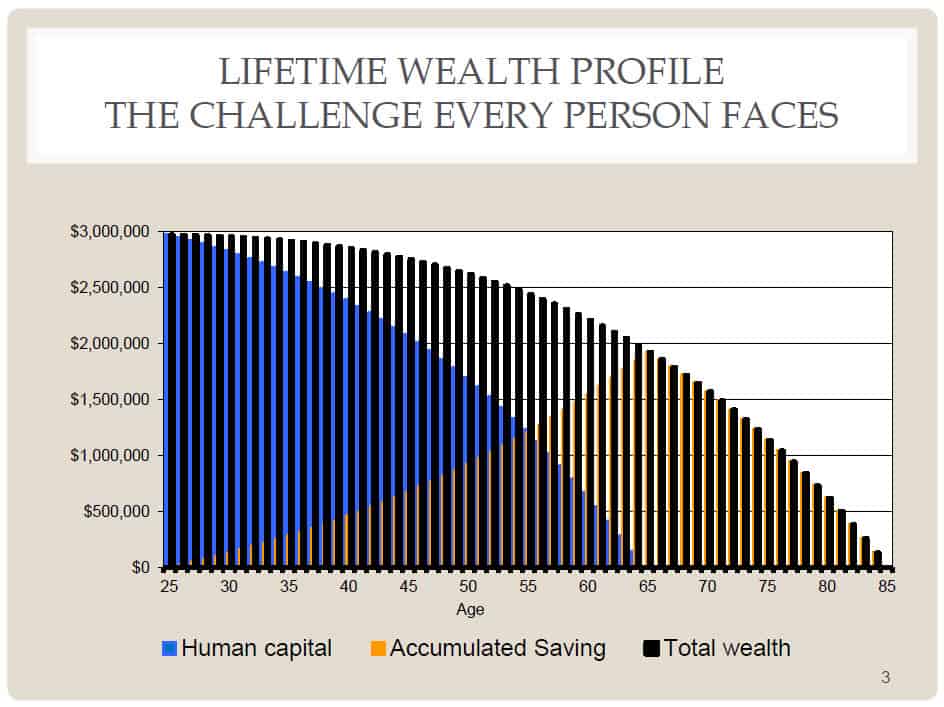

>>ZVI: So these are the sort of the big picture issues. If we look at this picture, what we see here is the sum of the two types of wealth. There’s human capital, add to that your savings and you see that your total wealth, the sum of the two is declining continuously over time. So that at the end, you’ve used up all your resources.

>>AUSTIN: Now Zvi, is it optimal then, you see at the end of the chart you’ve completely extinguished your total wealth upon your passing. I know my grandparents live that way, they said, “When we spend our last dime, then we’re going into the ground.” Not to be crass but that’s what they said. Is that what the model solves for? Obviously you can solve for bequest and what have you.

>>ZVI: As you might imagine, there are many offshoots of the basic model. So there’s what we call the bequest motive. And many people have a bequest motive. It can be added to the simple model. But this is the basic simple model with no bequest motive. And it’s a single individual. It’s going to be different if it’s a couple or a family, etc.

Elements of Life-Cycle Model

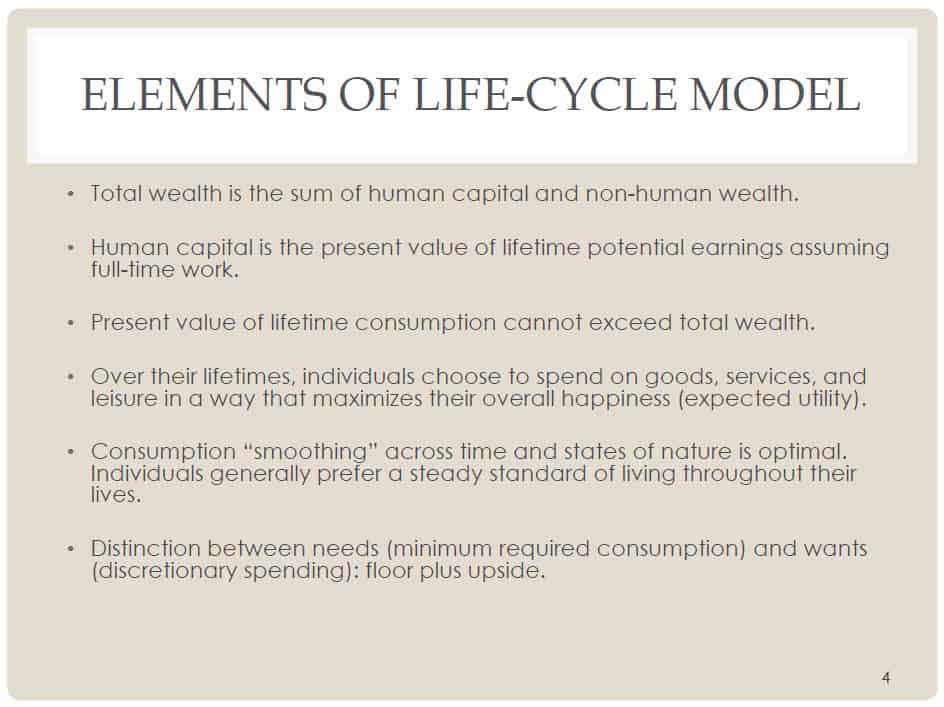

Okay. Now, what are the elements of the life-cycle model as developed in the economics literature? This is a rational model. It’s prescriptive. It’s how one should think about the issues. It is not taking account of irrational behavioral considerations. Those are very important when it comes to implementation. But in the pure economic theory of the life cycle, we don’t take account of that.

So first of all, element number one, we just talked about, it’s the notion that total wealth at any point in time, it constraints how much you can consume and it’s the sum of human capital and non-human capital, which in this model is the retirement savings plan. Human capital is a present value of lifetime potential earnings, assuming full-time work. The reason we define it that way is because the individual is going to choose to spend some of that on leisure. Now obviously, it’s not actual spending, it’s just not working two jobs.

The present value of lifetime consumption cannot exceed total wealth. That’s a very basic constraint. No free lunch. And we’re assuming that you can’t die with outstanding debt. No one is going to let you consume more than you can pay back. That too could be modified to some extent.

Over their lifetimes, individuals choose to spend on consumption of goods and services. They might give charitable contributions. The key point is the objective, the overall objective is to maximize their happiness, economists call it expected utility. It takes the form of a mathematical formula or a function that has to be maximized, because ultimately, the model has to be solved using mathematics.

>>AUSTIN: At some point, not for this discussion, but I’d love to see the mathematical formula for happiness. That’d be very interesting.

>>ZVI: Okay, it’s simple. It’s log of c, subscript 1, plus log of c, subscript 2. In other words, the most basic happiness function is logarithmic utility.

>>AUSTIN: There you go. We’ve all learned something today about happiness.

>>ZVI: And you want to know why? It’s because a log function has the following property. Your utility from additional units of consumption declines, declining marginal utility, and it’s proportional to how much you’re consuming already. A perfectly reasonable assumption to make was introduced to the literature, scientific literature by Daniel Bernoulli in the 1700s. But let’s not go off on a tangent. It’s too interesting to start doing now. Okay.

Consumption smoothing as a retirement income strategy

Consumption smoothing across time and states of nature is optimal. In other words, we will find in the solution to this optimization problem that the individual because of declining marginal utility will always want to smooth consumption out over time. Not have a feast and then a famine, but rather, so, you know, if you’re a sports hero and you have a short career, say 10 years of earning a lot, what our model would say is, save most of it for the years when income is probably not going to be as great.

What does it mean to smooth consumption?

Consumption smoothing is the economic concept used to express the desire of people to have a stable path of consumption. People desire to translate their consumption from periods of high income to periods of low income to obtain more stability and predictability.

>>AUSTIN: Well, and I do know some financial planners that do work with athletes and that is something that they try and do. You’re not going to be making millions of dollars a year forever. So, how do we smooth that consumption over the rest of your life?

>>ZVI: But here’s the other piece of it. You want to smooth it across potential states of nature. What does that mean? It means buying insurance against negative things that can happen. Disability, dementia if you are a football player, all sorts of contingencies that we call that smoothing across states of nature. In other words, assuring that you will be able to consume under adverse circumstances.

… there is a distinction between what you need, the minimum required consumption level and what you want.

Professor Zvi Bodie

>>Now, all too often, financial advisors who have athletes as their clients try and get them into risky ventures. It’s a very different story. I don’t want to bad mouth any advisers here, but before one worries about hitting the jackpot on the upside, I think most economists would say happiness means insuring against adverse events. So that’s in the model. And there is a distinction between what you need, the minimum required consumption level and what you want. That distinction between needs and wants, we have to teach our kids that from the earliest age.

And in reality, here’s where we can start thinking about how people actually behave. Wants have a way of turning into needs once you become accustomed to a certain level, standard of living. It’s a fact. So, as one approaches retirement for example, the goal for most people is to be able to maintain their standard of living because they’re very unhappy if they have to go down in terms of this.

>>AUSTIN: People like going up in terms of standard of living but not necessarily going down.

>>ZVI: Correct.

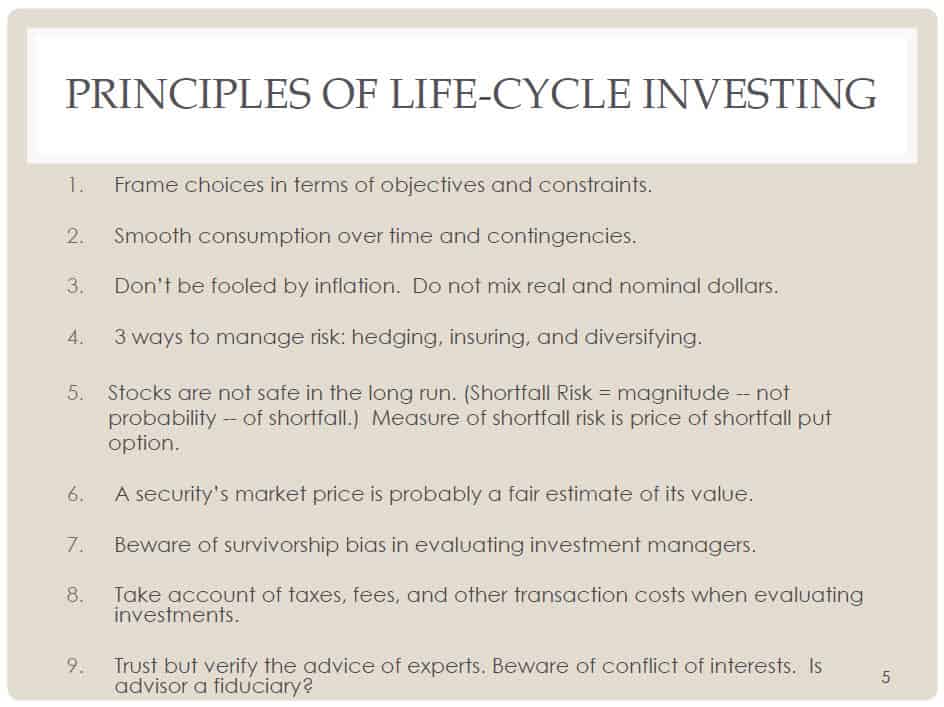

Principles of Life-Cycle Investing

>>AUSTIN: Those are the elements of the life-cycle model. We’re looking to smooth consumption over time, we talked about human capital and total wealth. Let’s get into the principles then of life-cycle investment.

>>ZVI: So, what are the principles? During this presentation, our objective is not to give the mathematical equations and show how to solve it using stochastic calculus. We just want to characterize what the solution is in a general sort of way. And these, I call these the principles of life-cycle investing.

So first of all, you always want to frame your choices in terms of objectives and constraints. That is to say it’s sort of the no free lunch principle. You’re going to be constrained by your total wealth, by your income and many other things. And the first thing you have to worry about in planning is that the plan you’ve come up with is feasible, not necessarily optimal, but feasible.

… the first thing you have to worry about in planning is that the plan you’ve come up with is feasible, not necessarily optimal, but feasible.

Professor Zvi Bodie

>>AUSTIN: How does one even know if it’s feasible though without good advice?

>>ZVI: That’s why you work with an advisor and you look at your assets and you look at your income now and potentially in the future. So you do that analysis and that’s very valuable. Very few people do it unless they are dealing with an advisor. You kind of have to do some of it at tax time. That’s why I personally as a practical matter think that financial planning is best done at tax time because most people, my wife being an example, hate finance more than going to the dentist. They just hate it. So, you try and minimize the pain.

Smoothing consumption over time and contingencies, we’ve talked about that. You’ve got to frame the decision in that way, there are going to be a sequence of decisions. We set certain goals, and don’t be fooled by inflation, this is my third.

Use “real” rates (i.e. don’t be fooled by inflation).

Professor Zvi Bodie

>>AUSTIN: Yeah, some people know you as the TIPS guy or the I bonds guy. You’re like Mr. Inflation.

Use TIPS and iBonds for a safety-first retirement income strategy

>>ZVI: My doctoral dissertation, which was written under the supervision or the guidance of Bob Merton at MIT was on hedging against inflation. And at that time, there were no I bonds or TIPS, treasury inflation protected securities. So, what could you do? There really was no way of protecting yourself against inflation. That has all changed as a result of these innovations. The US Treasury was responsible for issuing these bonds starting in 1997.

So, it is very important, however, even in the absence of a way to protect yourself against inflation, to simply measure things correctly because, for example, if you’re looking at your resources in the future, and let’s say you’ve got Social Security and you’ve also got some sort of pension plan. Social Security we know has a cost of living adjustment clause. So it’s in real terms. So if you expect to get say $1,000 a month, that’s going to go up with inflation. We call that a “real” variable.

What is the difference between real and nominal?

In economics, nominal value is measured in terms of money, whereas real value is measured against goods or services. A nominal value does not adjust for inflation, and so changes in nominal value reflect at least in part the effect of inflation.

A real value focuses on the basket of goods or services without the effect of inflation.

This makes planning difficult, and comparisons mixing both real and nominal values is a grave error: it’s apples and oranges.

For instance: comparing the amount of a pension (typically without an inflation adjustments) with the amount of a Social Security benefit (which adjusts with inflation) might substantially overstate the value of the pension.

For another example, consider traditional bond yields which include expected inflation. Only special bonds in the U.S. (TIPS and iBonds) remove the risk of inflation by adjusting for actual inflation. So to compare their yields is meaningless. They have different risks and different returns.

>>ZVI: If I’m going to get a pension, it typically will not, in this country, will not have a cost of living clause. So whatever dollar amount it is, it’s going to stay fixed. In nominal terms, we call that a nominal variable. If you’re trying to judge whether you’re going to have enough income to replace your earnings once you retire, you can’t add those two things. So, security and the nominal pension, because they’re apples and oranges. One is going to go up with inflation, the other isn’t.

So one way to approach it, now, the outcome of this problem is that financial planners, for example, who make this error are telling people that they’re going to be better off than they really will be. So, you’re building false confidence.

>>AUSTIN: So, because the nominal income is not going to go up with inflation, the real income like Social Security is so you’re protected there. I think this rolls into your next principle about inflation is a big risk in retirement, especially if you’ve got nominal cash frozen, you’re not managing that risk. Remind us, how does one manage risk?

>>ZVI: Well, first of all, let me make this following point. If you wanted to have a real pension adjusted for inflation, there are some insurance companies that will sell it to you today. But the starting level is going to be two thirds if not less of the nominal annuity. In other words, you’ll get a lot less at the beginning because it will be going up with inflation. And if you compute your replacement rate of salary using the lower number, you’re getting a more realistic view of your income in retirement.

So I say this, I emphasize this point because I know a lot of advisors, many advisors who make this mistake. They don’t automatically adjust. There are three ways to manage risk. Very important. Ask a typical advisor or anyone who is financially illiterate, how do you manage risk? Their gut reaction, wake them up in the middle of the night and put the question to them, they’ll say diversify. That’s not the only way to manage risk.

Hedging and Insuring for better retirement income planning

Investment risk or inflation risk, any kind of risk, there are three ways. And the other two are actually just as important if not more important for goal-oriented investing. One is hedging, and hedging simply means finding out what the safest way is to invest for a particular goal. So if it’s retirement, it’s going to be inflation protected bonds, a portfolio duration matched, an immunized portfolio. These are terms that are used in the institutional world to say you want to lock in, you get out of stocks and into these bonds that lock in a certain stream of real inflation adjusted income.

What is hedging?

Hedging simply means finding out what the safest way is to invest for a particular goal. So if it’s retirement, it’s going to be inflation protected bonds (iBonds or TIPS). Hedging doesn’t cost anything because you’re just changing your allocation to U.S. Treasury bonds. It is unknown whether you are going to earn a lower rate of return because you are moving from a risky asset (uncertain return because of inflation) to a guaranteed fixed rate of return.

What is “matching”?

The safest portfolios have assets matched to liabilities.

Example 1. If your retirement goal is to rely on $4,000 per month (adjusted for inflation) and your Social Security benefit provides that, then you have matched your assets with your needs and you can sleep comfortably. It’s as safe as you can get.

Example 2. You have a ladder of bonds that mature to satisfy your needs at that time. That matching, but not quite as safe because you remain vulnerable to inflation. Note that inflation risk can be removed if you use iBonds or TIPS, but you might still have longevity risk of living longer than these savings.

Example 3. You have $1.2 million in stocks and bonds and intend to draw 4% to satisfy your needs (which are still $4,000 per month for 30 years. That’s a weaker form of matching because success depends on historic probabilities and you have no guarantees.

Risks include stock and bond market returns, the sequence of those returns, and the possibility of outliving your money.

Another variation of this plan is to spend some of the accumulated savings to buy (an inflation adjusted) annuity to cover a minimum requirements floor and then investments for spending above that.

>>ZVI: That’s hedging and it doesn’t cost anything because you’re just changing the allocation of your asset. Now you’re going to earn a lower rate of return, maybe, maybe not, because you’re getting out of something that’s risky and has an uncertain return. You’re getting into something that has a fixed rate of return.

Insuring is different from hedging in that you have to pay a premium upfront, you have to give up something in order to eliminate the downside, but you retain the upside or most of the upside. That’s a very important type of risk management. In investing, that would be buying a put option on a stock portfolio to eliminate the downside risk. It cost you something, you’ve got to pay for the put option.

What’s an example of insuring?

Insurance is to pay to eliminate the downside. For example, a risk that we all have is that we might live longer than average, and outlive the money we have saved. An annuity is a form of insurance against this — longevity insurance. You exchange a lump sum of money for a stream of money that will last your entire life.

You benefit from pooling money. When you buy fire insurance for your home there is a small premium, and the people who don’t have a fire subsidize paying for those who do. Similarly, with an annuity, those who live shorter lives subsidize those that live longer than average.

Your Social Security benefit is an annuity that, additionally, adjusts to protect you from inflation. Many point to the great benefit of delaying your Social Security benefit until age 70 to maximize this benefit.

>>ZVI: So these are the three dimensions of risk management, and in the usual discussion of asset allocation around retirement planning, the only thing you hear about is diversify, typically.

What is diversifying?

Diversifying is the traditional approach to risk management. It refers to both spreading risk (don’t put all your eggs in one basket) and to taking advantage of poorly correlated returns (Modern Portfolio Theory). Additionally, it attempts to address life-cycle needs with rules-of-thumb like “Own your age in bonds.” However, this does not guarantee retirement income, guarantee sufficient returns, protect against inflation, nor eliminate longevity risk.

>>ZVI: Number five, very important principle, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that stocks are safe if you have a long run horizon. This is misleading advertising by the investment industry. Widely believed, including financial advisors who say if the short run you’re investing for short run, stocks are risky. Long horizon, you can’t go wrong. They’re going to beat bonds, for example, by a lot.

Well, if that were certain, if it really was sure, then why would stocks offer a risk premium if they’re not risky. It would be an arbitrage situation. You’d always want, any long-term investor would want to swap bonds for stocks, push up the price of stocks. It’s an impossibility, even from a theoretical point of view.

I have written a paper in which I’ve proved using option pricing theory and practice, that if you want to guarantee a stock portfolio against the shortfall relative to the safe rate of return, the price, the cost of that put option actually increases with the length of your time horizon, doesn’t decrease, it increases with the square root of the time, the horizon date.

It’s a fallacy to believe that the risk of stocks goes away in the long run. I can’t emphasize that enough.

It’s a fallacy to believe that the risk of stocks goes away in the long run.

Professor Zvi Bodie

>>AUSTIN: And Zvi, I know we’ve talked about this in the past, if the target date funds, for instance, in the early years, they’re very heavily invested in equities. Is that violating this principle?

>>ZVI: No, it’s not because in the early years, most of an individual’s wealth, a middle class person, average employee, it’s human capital. The amount in their retirement account is tiny compared to the human capital. Now, if their human capital is very risky, well now we’ve got an issue. But for most people it isn’t, certainly not compared to the stock market. And so, you can afford, as it were, to have a lot of risky stocks in that tiny savings. Now, as you approach retirement and you have a good idea of what your target income level is, that’s when you want to hedge.

Number six, a securities market price is probably a fair estimate of its value. Well, don’t expect to find bargains lying there on the stock market. Maybe someone who spends 24 hours a day and is really a sharp analyst, a Warren Buffett or whoever can beat the market. Most of us can’t and we don’t know who can. So, we’re just better off assuming that there are no bargains out there, everything is fairly priced. Doesn’t mean you don’t want to invest in the market as a whole. That’s a very important principle.

Beware of a survivorship bias in evaluating investment managers. Now, this is a pervasive problem that really fools a lot of people. So you typically will read advice of the sort, look at a firm’s track record to determine whether the fund can beat the market or not. Well, most of the reports that you see in the newspaper and so forth are based on a management company’s existing funds. They don’t tell you which funds have been shut down over the reporting period. And it’s not a random selection. It’s the ones that did badly.

In scientific studies that are done, university thesis, doctoral dissertations and so forth, we correct for survivorship bias. There are various ways of doing this. But if you just read the reports in the newspaper, the SEC does not require companies to correct for survivorship bias. So you’re getting a meaningless picture of performance. That’s not understood by most people, and it’s very important. Certainly important for their financial advisor to recognize that.

Take account of taxes, fees and other transactions costs. Well, I don’t have to tell advisors how important that is. Trust but verify the advice of experts. Typically, people are not experts. I know for example, when I take my car in for repair, the garage can tell me anything they want, and I’m going to have to trust them. I could take it around to several and get opinions and prices, but I have to find a garage that I trust and ask questions. There is such thing as trying to verify that you’re getting trustworthy advice.

Same thing goes, I know I have this problem with my health care. I’m getting up in years. Various body parts are wearing out. I don’t exactly know what to do. So what do I do? I see a doctor, he’s the expert or she’s the expert. And I say, “Doc, if you were me, what would you do?” And the doctor typically says, “I can’t tell you what to do.” It’s the same thing that the financial advisor has to say when asked how much risk should I take.

>>AUSTIN: So, find a good advisor. There are a lot of good advisors out there that we work with.

>>ZVI: I follow the rule of fiduciary. I would always say find an advisor who swears to the fiduciary standard because at least in principle, they’re legally bound to put your interest ahead of their interest. And brokers for example, typically don’t have, they have a lower standard, suitability standard. That’s important.

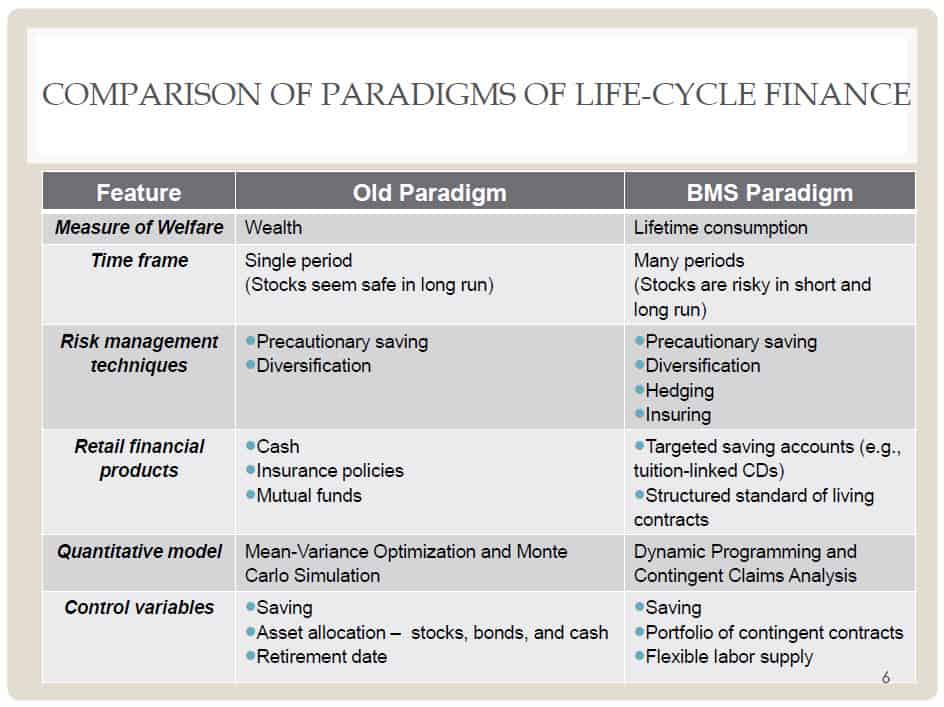

Retirement Income Planning with New Paradigm

>>AUSTIN: So those are the principles of life-cycle investing. Now let’s compare if you will, Zvi, for our audience tuned in here online. How does your approach, really, the Bodie-Merton-Samuelson life-cycle paradigm compare to kind of the old school tends be more prevailing paradigm still in the markets today?

>>ZVI: So in the early 90s by which time I was already a full professor at Boston university, I came to Bob Merton, I said, “You know what, let’s take your model and build in what I think needs to be a part of the standard approach to the life-cycle.” And that is labor, leisure choice. And we worked on this together with Bill Samuelson, who is the son of Paul Samuelson and a faculty member at BU.

We came up with a model which has kind of become the standard model for the life cycle adopted by just about any theorist who writes on it. They may elaborate on it, but at its core, it’s the Bodie-Merton-Samuelson model. How does that differ the theoretical model from the existing, what I call old paradigm? And also we’ll talk after this about how you implement that. In other words, what does it imply in practice?

So first of all, what is the measure of welfare? Well, in the old paradigm, which starts with the work of Markowitz and Tobin in the 50s and 60s, it’s wealth. And what is being maximized is the expected utility from end of period wealth. That turns out, I mean, for some purposes, that’s fine. Very few purposes. In the real world where you’ve got many periods and you’ve got a retirement decision to make, it’s lifetime consumption. And in mathematical terms, you’re maximizing utility or happiness from consumption in every period of your life.

AUSTIN: And Zvi, remind our audience, it seems like there would be different measures of risk as well if you’re managing towards wealth that may be the volatility of your account balance, but in your paradigm, what is the metric of risk then?

ZVI: Yes, absolutely. One of the things that Bob Merton harps on and he made this point early on in his earliest papers, is that there can be and often is a big difference between measuring risk in terms of your consumption or measuring risk in terms of wealth. In other words, wealth can fluctuate or may have to fluctuate in value in order for consumption to be smooth. Well, that gives rise to all sorts of hedging demands. That’s really a key insight of Merton’s model long before I started writing anything with him.

The timeframe in the old paradigm is a single period. Now, might be a very long period. Like today and 30 years from now, retirement. And what you’re trying to do in this model is maximize expected utility from end of period wealth. Well, a problem with that approach is that it often makes stocks the risky major risky asset seem less risky as you increase the length of the horizon. Why? Because if you’re using average rate of return as the thing that’s varying, the longer the time period, the narrower the range of possible values of average rate.

But that’s an illusion. That is to say it’s not, the right way to measure the risk is the short fall risk, the cost of insuring against the shortfall. That’s a problem with this paradigm and practical term’s a very big problem. And in the BMS paradigm, Bodie-Merton-Samuelson, many periods, in fact in the limit, it’s continuous trading so that you’re frequently revising the portfolio, whoever is managing the portfolio is revising it. And you see immediately the stocks are risky both in the short and in the long term. And that’s where risk management becomes crucial.

… you see immediately the stocks are risky both in the short and in the long term. And that’s where risk management becomes crucial.

Professor Zvi Bodie

>>AUSTIN: It seems like a more dynamic approach, right? In the BMS paradigm, you really have to be dynamically re-balancing and adjusting towards the goal.

>>ZVI: Yeah. Suppose this were a flight from here, Austin to Boston. And one approach is to say, all right, we’re going to take off, head in a certain direction and that’s it. Four and a half hours from now, we’ll hit someplace, hopefully it’ll be Boston. Versus from the time you start out, you’ve got Boston in your sights and you’re adjusting to make sure that you get there. Okay?

Risk management techniques that are employed. Well, in the existing or old paradigm, it’s save as much as you can, so precautionary saving and diversification. That’s it. In the new paradigm that I’m advocating, it’s those two things plus hedging and insuring, very important. What are the retail financial products that are the objects of choice? Well, in the existing paradigm, what is it? Cash, stocks and bonds, the three mutual funds and insurance policies to manage some of the risks. That’s part of the existing paradigm.

… in the old paradigm, it’s save as much as you can, so precautionary saving and diversification. In the new paradigm that I’m advocating, it’s those two things plus hedging and insuring, very important.

Professor Zvi Bodie

But in the new paradigm, you’ve got targeted saving accounts. In other words, specific hedging instruments that are designed to hone in on a particular goal. So it might be inflation link, retirement income, or it could be tuition accounts, health savings accounts, things that have specific goals. And those are managed in a different way. Those are hedges.

I have your structured standard of living contracts. The only thing that today takes that form are structured products like market index CDs for example. But very few people use those. Very few financial planners are using those. I think they could be used a lot more.

All right. Quantitative model. The existing paradigm is really mean variance optimization. It’s Markowitz with Tobin thrown in for the safe asset, Monte Carlo simulations of outcomes. This is much more high powered mathematics. It takes a lot of study to master it. Right now it’s financial engineers, but people working in institutional risk management who are up to speed in the mathematics of it. You really have to have, say, an undergraduate major in math and your learning dynamic programming and contingent claims analysis, it’s Mertonian mathematics and finance. We’re not getting into it in this discussion.

What are the control variables? Well, the old paradigm, it’s how much you save, how you allocate your assets, stocks, bonds, and cash, and adjusting your retirement date. Those are the control variables.

In the new paradigm, you’ve also got a portfolio of contingent contracts. In other words, you can actually have a demand for products that have certain payoff structures. The example that I would give in the framework of retirement saving is income annuities, lifetime income annuities, which clearly are beneficial to at least people who don’t have a bequest motive.

So, someone who’s single wants to have as much income as he or she can get while they’re alive but doesn’t really have any utility from income that’s left over after they have passed. Well, you want to make sure that that person is making use of that contingent contract. For the same amount of retirement saving, you can get more income out.

>>AUSTIN: Your paradigm seems much more holistic. It’s also much more sophisticated and complicated. I don’t know a lot of advisors out there that are doing contingent claims modeling. I certainly am not. Where does that all lead us? So you’ve got a very sophisticated model that targets the right goals. How can advisors actually harness this or we as a financial services industry, how can we use this in practice?

>>ZVI: Okay. So first of all, you got to be careful about the terminology you use. So we don’t want to say contingent claims, we want to say insurance contracts. Because that’s basically what they are. Although, if you’re talking about call options, it’s not really insurance, it’s the upside. You’re buying the upside. But the key point and even options are something that can be explained to people because options exist all over the place in everyday life.

So, terminology is very, very important. Certain terms become like dirty words. Got to stay away from them because people are going to think, oh oh, this guy doesn’t know what he’s talking about. I get that a lot. I do know what I’m talking about, or at least I think I do. So, that’s a key issue.

But one has to explain in simple terms. I don’t think there’s anything that I presented here that couldn’t be understood or explained in a way that an average person can understand, if they’re willing to listen. Now of course there are a lot of people just don’t want to know. They are allergic. I understand that perfectly because there are areas of my life where I tune out the minute the discussion gets technical.

I mean, a good example is controlling my television set in the age of remote controls and Netflix and streaming this and streaming that and direct TV. I just don’t have an interest in mastering all of that. All I want is when I press the on button, the television should turn on, and when I press end, it should turn, you know, I have limited demands. But we live in a complicated world, and even for something like that, you can’t be completely ignorant. There’s a certain minimum amount that you have to know. I want to learn it from somebody who’s not trying to sell me on a particular product or a solution.

Worry-free Investing

>>AUSTIN: I think you get into this in your next slide, talking about how we can use life-cycle finance. But for advisors and for the rest of the industry, how do you see this all playing out?

>>ZVI: I do think that one has to rest on the notion that there’s a science here, that there is an underlying science. It’s not all baloney. And that there are people who want to be faithful to the science. So here’s what I think, this is my optimistic forecast for the future. Life-cycle investing will be about choosing among features of products designed for consumers by financial engineers. But it should be said as a general rule, that when a product is easy for the consumer to use, it’s harder for the engineers to design and maintain.

It’s not always the case, but it certainly I believe is the case with financial products. And it’s easy to build in complexity that doesn’t really help the consumer. So, regulators have to be taught how to think about this stuff. We have a long way to go in those terms. I could give you examples of arguments that we’ve had with the regulators, but such is life. There will be progress I think.

I think the financial crisis was caused by lousy regulation and consumers not understanding what they were doing, taking out mortgages. Ignorance played a big part in that financial crisis in my view. So, I’m being optimistic here. Technological progress will make these products affordable for middle-class consumers, not just the wealthy. So a well-designed product given the technological advance, a lot of it is going to depend on FinTech, financial technology that drives costs down. Not always, but in most cases.

So, there’ll be some combination of financial technology in the mix of financial advice. It will not replace the financial advisor, that’s for sure. I like to give the example of Financial Engines. The very first FinTech company in the area of life-cycle or retirement advice, it was designed to be a do-it-yourself kind of robo advisory that was offered by firms to their employees who were making decisions on their retirement plan.

And today, 30 or some odd years later, 25 years later, you got to Financial Engines, they still have the technology, but the first thing it says on the screen is call this number for assistance. They don’t want you to try it on your own. They don’t think you’re likely to do it, but if you do, you’ll probably give up. So right off they say, call an advisor.

>>AUSTIN: So we have about five minutes left. I want to make sure, because this is really what you’re known for, is the safety first portfolio. So, if we could skip ahead two slides to, let’s just have professor Bodie walk us through what a safety first portfolio, how you might calculate and think about that vis-a-vis a retirement goal.

>>ZVI: This is the theme of my book, which was supposed to be a mass market bestseller.

>>AUSTIN: Still working on it.

>>ZVI: Still working on it. Worry Free Investing. You start at, let’s say the goal is retirement. What are you looking for? You’re looking for an inflation protected income for life that allows you to sustain your customary standard of living in the latter part of your working life, and to cover the gap between your desired income level and your social security benefits. That’s a reasonable statement of a goal.

Key retirement income strategy: save a lot!

Now, how should you, what are the steps in implementation of this approach? Well, first of all, compute how much you’d have to save, the required contribution rate, if you took minimal risk. You invest in TIPS with match maturity. It requires a certain savings rate, and let me assure you, with the real rate of return being less than 1% on a pretax basis, you’re going to have to save a lot. It’s not going to be a happy picture, particularly compared to the advice that people have been getting when they assume five or six or 8% rates of return. So you’re going to have to save a lot.

You’re going to have to save a lot.

Professor Zvi Bodie

Now, if you decide, this is the term structure of real interest rates, okay, just the other day, and you see they’re all less than 1%. And this is what it looks like as a picture. There’s a maturity of five years, 30 years. You can see it’s flat. Expected inflation is this difference between the nominal and the real treasury rate about 2% per year, all the way out to 30 years.

>>AUSTIN: 2% break even inflation, give or take. 70, 80, 90 basis points of real return, that’s what you’re talking about.

>>ZVI: How is it going to change in the future, we don’t know.

>>AUSTIN: This is today’s numbers.

>>ZVI: I don’t expect a real yield curve to be much different in years to come. I actually think it’s close to zero. It’s between zero and 1%, and it’s going to stay there. How do I know this? I don’t. But if you look back, except for the period when tips first came out and the market was not used to them and the yield was 3% real terms, three and a half percent, that disappeared within a matter of a few years. I don’t think it’s going to come back. So we better get used to this as the safe rate of return.

Now, there may be a risk premium on equities of four or 5%, but that’s a premium for taking risk. So here’s my question. If you are going to take risks and let me go back, we found the contribution rate, the amount of savings on a safety first solution, how much risk are you willing to take? Well, let me just ask this question. Do you need to save more or less if you’re going to take risk? Not clear. You can’t bank on earning the risk premium. It might go the other way. So it’s not clear that you can save less.

Do you need to save more or less if you’re going to take risk? Not clear. You can’t bank on earning the risk premium. It might go the other way. So it’s not clear that you can save less.

Professor Zvi Bodie

We all do save less by assuming for 6%. Why? Because if you tell people how much they actually have to save in a no risk world, they might not want to save it all. They might get discouraged. Okay, so they take risks, but don’t tell them that there isn’t any risk because it could go against them. And you’re going to have to adjust the portfolio as you go along, and change your goals if things do.

Let’s say you’re flying from here to Boston. You hit a rainstorm, a windstorm, whatever, you’re going to have to adjust. Start withdrawing income at the target date. That’s the steps in the process.

>>AUSTIN: And I think that might be all that we have time for today. It’s just so exciting to have you here. Thank you so much on behalf of all of us, Professor Bodie.

>>ZVI: My pleasure, and thank you to all those people who asked questions.

>>AUSTIN: I think we covered most of it. Definitely, if you download the slides or you want additional information, go to zvibodie.com.

Printing, Downloads, and Additional Resources

Book Review: Risk Less and Prosper More: Your Guide to Safer Investing by Zvi Bodie and Rachelle Taqqu.

Book Review: Safety-first Retirement Planning by Wade Pfau

Video: Interview with Professor Zvi Bodie at Boston University on Worry Free Investing.